WESTWOOD—Refrigerators are among those things we don’t think much about until the power goes out. We have all put our lightning reflexes to the test during an outage, opening and closing the fridge door as quickly as possible to “keep in the cold.”

That gives us a small sense of what things were like a century ago, in the era of the icebox.

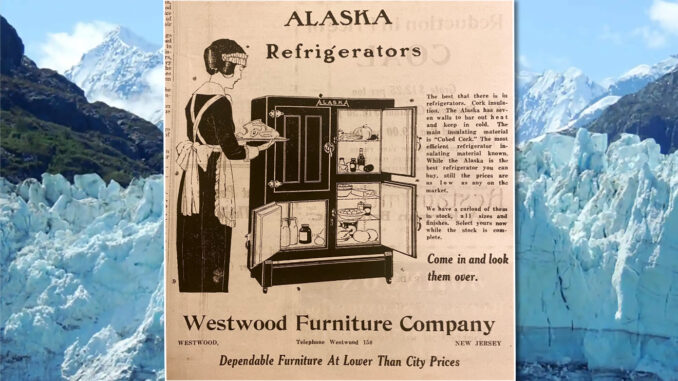

The advertisement featured on this page dates to a century ago. The Westwood Furniture Company placed it in the Park Ridge Local, a weekly newspaper, on April 12, 1924. The store was selling Alaska brand refrigerators, iceboxes that featured a thick wall of cork as the insulating method. The exterior cabinet was oak.

Until the 1930s, most people were still using the trusty old icebox, and there were many models on the market to choose from. Constructed of wood or metal and featuring insulated compartments, large blocks of ice would be placed inside to keep food cold. When it melted (there was a drip basin for this purpose), it would be replaced with a fresh block.

In those days there were businesses that harvested ice in the winter and stored it for just this purpose. Cut from lakes and ponds and kept in ice houses insulated with sawdust, the supply could last all year. By the 1920s there were also factories producing cleaner artificial ice.

The icemen made regular rounds, first with horse-drawn wagons and later with trucks, delivering blocks of ice for people’s refrigerators. Children would follow behind on hot summer days, hoping for discarded chips of ice. Imagine what they would think of today’s built-in ice dispensers!

Because cold air descends and warm air rises, the ice block would be placed in a top compartment and cold air would circulate downward. How long it lasted depended on how often the door was opened—the less, the better.

Cork insulation was advertised by the Alaska Refrigerator Co. as a top method to help ice last longer. Other models historically used sawdust, straw, and even seaweed as insulators. At a cost of about $35 in the early 1920s, these appliances were vastly more accessible to the average American than their electric counterparts.

The early 20th century had seen plenty of innovation in refrigeration, particularly when it came to electricity. There was a race to produce a product that would win the public’s favor, one that would convince the masses to ditch their iceboxes in favor of electric appliances. Many companies tried, but the technology just wasn’t there yet. By the 1920s electric models were used commercially, but the market had not yet reached a point of widespread home use. For the homeowner, the appliances were either impractical or unaffordable.

Some electric refrigerators of the time had mechanical parts that were separate from the cold box itself, and these would be located in a basement or adjacent room. They broke down and had to be repaired regularly. Early models used toxic gases as cooling agents, and leakages caused several fatal accidents.

In addition to those issues, in the early 1920s the cost of an electric refrigerator was simply out of reach for the vast majority of Americans. Considered a luxury item, the appliances ran about $750, which was higher than the cost of a Ford Model T. The average annual income in those days was about $3,000.

In the 1930s, electric refrigerators became more reliable and affordable. Americans began happily giving up their drippy iceboxes in favor of the new modern convenience.