CLOSTER, N.J.—In the winter of 1974, a debate between historians and impassioned citizens culminated in a 175-year-old structure being cast out of Closter.

The building in question went by a couple of names. To some, it was the Parsells tenant house. To others, it was the Vanderbeck slave house, an eyesore and a disturbing reminder of a dark time in history.

The five-room cottage at 611 Piermont Road, built around 1800, had sat largely unchanged and all but forgotten until being thrust into the limelight in August of 1972.

At the time, 84-year-old Mrs. Helen Cole, widow of former police chief Marcellus Cole, had been living on the property. She sold it to Howard Savings Institution, which planned to build a bank there (they eventually did, and now it is the Wells Fargo branch).

Walter Parsells had first built a sandstone house on 34 acres on Closter New Road (Piermont) in 1795. That house is still standing today, across from the High Street intersection. The wooden cottage was built next door.

In 1806, Walter’s brother, Jacob Parsells, married Cornelia Blauvelt. After Jacob’s death in 1833 Cornelia was married twice more, the last time to John Vanderbeck. Thus, she became Cornelia Vanderbeck. In the second half of the 19th century, Cornelia and her son used the main house as a tavern serving stagecoach travelers on the route between Englewood and Nyack.

At some point the cottage became known colloquially as the Vanderbeck slave house, rumored to have been used as a dwelling for slaves.

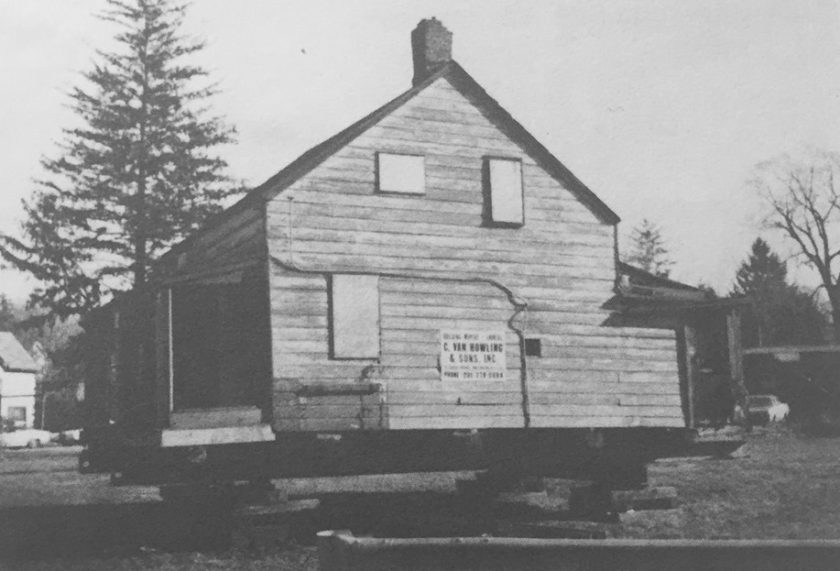

In 1973, bank officials, acknowledging the history of the structure, offered to give the cottage for free to anyone who would pay to have it moved. When nobody came forward, in mid-December it was temporarily moved to Lone Horseman Park at Closter Dock and Piermont roads.

By the winter of 1974, residents were starting to speak out against the structure as a symbol of slavery. More than 25 black residents came to a council session that Jan. 9 and demanded it be removed from the park. A petition gained over 100 signatures from black and white residents alike. People called it an eyesore, distasteful, and an insult to the black residents of Closter.

And yet, as researcher Madeline W. Hampton of the Bergen County Historical Society discovered at the time, there was no record of the cottage ever housing slaves. Along the same lines, another local historian, Joan Winkelhoff of the Pascack Historical Society, studied old tax records and found that the property was never taxed as having slaves. It seems the term “slave house” had somehow gotten attached to the structure and stuck in the public’s perception. The more likely reality, historians asserted, is that the little cottage housed indentured servants or sharecroppers.

In the end, the house was saved—but not in Closter. Walter Muller, a builder with knowledge of restoring old properties, had it moved to his private property at 480 Sicomac Ave. in Wyckoff at the end of February, 1974. The little cottage made the 16-mile journey on a flatbed trailer. It’s still standing there today, beside the main house on the site.