CLOSTER, N.J.—Imagine driving into a new town and trying to find your way to a friend’s house without the use of street signs or house numbers. That’s what anyone visiting Closter had to contend with up until 1940.

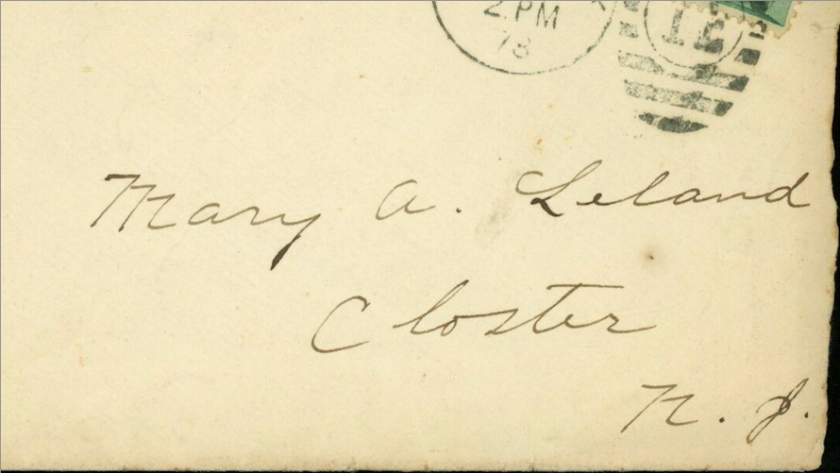

For much of its 200-year history, the Northern Valley had been isolated and rural, with farmhouses dotting the largely undeveloped landscape. With few people in town, everyone knew their neighbors and where they lived. Incoming mail, which was picked up rather than delivered, listed only the recipient’s name and “Closter, N.J.” in those days before house numbers or zip codes.

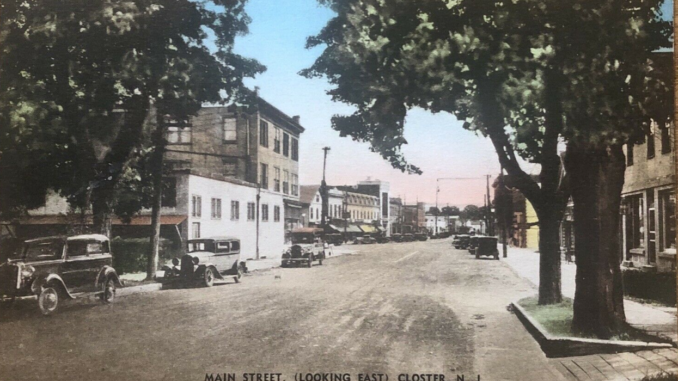

Eighty years ago, in July of 1939, the people of Closter decided it was time to modernize. The developing borough had mostly shed its rural past, but the lack of street names and house numbers still made the flourishing suburb nearly impossible for outsiders to navigate. In 1939, only a few of the main streets bordering the central business area had signs showing their names, and not a single house had a number.

The setting of house numbers began the following year, in July of 1940, and was taken on as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project. The WPA, which lasted from 1935–1943, was a nationwide agency that provided jobs and income to the unemployed during the Great Depression. Closter’s borough hall had been built through WPA labor in 1938 and is still in use today.

In 1940, WPA workers were assigned to call each landowner in Closter and notify them of what their house number was to be. It was then up to the homeowner to post the number on the dwelling.

The use of WPA labor represented a huge cost savings to Closter. Seven WPA workers were stationed at an office within the borough hall, and Closter had only to pay for stationery and minor office supplies. The federal agency paid all of the men’s wages.

The project included measuring all lots in town, both developed and vacant, numbering them on a systematic basis, obtaining descriptions of all properties, creating property maps, and indexing house numbers.

That same summer, the borough got underway with its street sign program. This was not a WPA project, but, rather, was funded by local taxes.

Starting from the most widely used thoroughfares and working outward, the borough purchased 43 new signs—and steel poles to hold them—in June of 1940 at a cost of $9 per sign (imagine that price today!). These were installed in August of 1940, with the poles preceding the street name plates by several weeks. In the ensuing years, additional signs were added on lesser-used streets until the entire borough was covered.