BY KRISTIN BEUSCHER

OF NORTHERN VALLEY PRESS

Northern Valley, New Jersey — In 1939, a woman named Ellen Tilton Holmsen was kicked out of Harrington Park for the offense of wearing pants in public.

Holmsen was a woman ahead of her time, and you might even say she marched to the beat of her own drummer. With a distaste for dresses and a predilection for going barefoot, she had caught the public’s attention once or twice before.

This was an era when a woman wearing trousers was considered not only unconventional, but also shocking to some. Pants and shorts would have been considered acceptable for certain activities—like lounging on the beach, doing some types of work or playing certain sports—but casually wearing them around town would have been enough to leave more traditional types clutching their pearls and gasping at the offense. (Perhaps it could be compared to wearing a bikini today; accepted at the pool, but not so much at the supermarket.)

A Long Island socialite, Holmsen was born in 1907 and grew up in high society in the Hamptons. She was the daughter of Newell W. Tilton and Mildred Olive (Bigelow) Tilton, and the stepdaughter of Herbert Claiborne Pell, the United States’ minister to Portugal during Franklin Roosevelt’s administration. In 1927 she married Nicholas Holmsen, whose father was a general in the Russian Imperial Guard, and whose mother was the lady-in-waiting to Tsarina Alexandra of Russia.

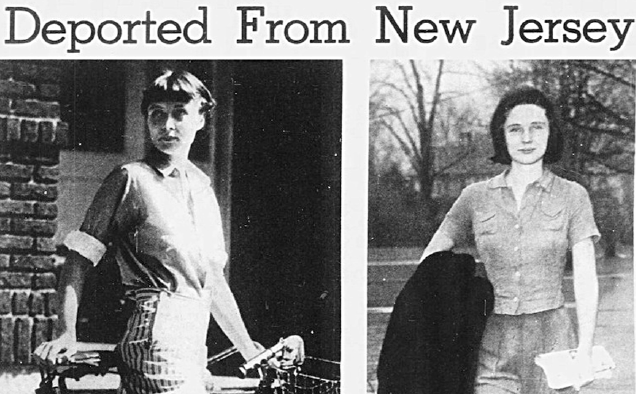

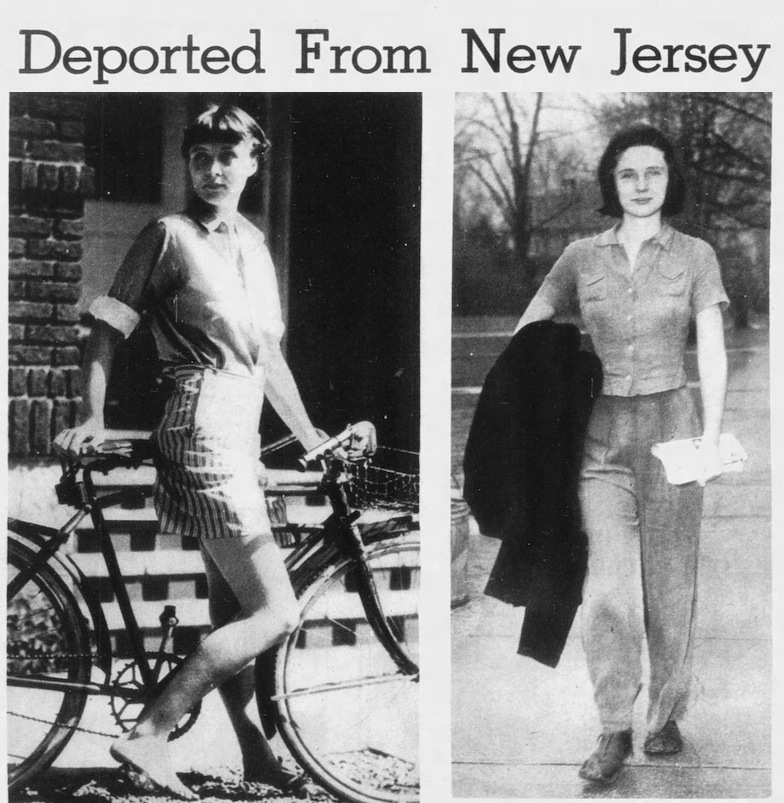

Two of the hundreds of news headlines that followed Holmsen’s 1939 ejection from the Northern Valley. The story was syndicated nationwide.

Holmsen was a proponent of what she called the “simple life,” advocating closeness to nature and rejecting complicated or constricting garments, societal conventions, false modesty and unnecessary material possessions. Pants, she said, were the most practical and utilitarian of clothing choices.

“I am opposed to any and all conventions that are contrary to nature,” she said in 1939. “I am an advocate of health and freedom and believe that one should live to gain those ends…Compliance with all natural laws is my aim in life. It was not intended that we should be enslaved to a lot of cut and dried forms of dress, habits and marital relationships. It was not intended that mankind should be enmeshed in a net of conventions.”

Perhaps there was something to all of that, because Holmsen ended up living to be 97. But while she relished simplicity, her wardrobe caused quite a few complications in her lifetime.

She first attained notoriety in Reno, Nevada, in 1934. She had gone there to obtain a divorce, and was thrown out of the court room for appearing barefoot and in shorts. She later returned in black trousers, a man’s shirt and tennis shoes, and was sent away again. She wasn’t able to obtain her divorce until she acquiesced and appeared in court in a simple black dress. Days later, a Reno restaurateur banished her from his place for the same offense of showing up in shorts. The only reason a woman would dress that way was to be “picked up,” he said, and his establishment wasn’t that sort of place. Both of those incidents made national headlines.

By 1939 Holmsen had moved back east and was living in Bergen County. Looking to make a move from a small bungalow she was renting on Spring Valley Road in Maywood, the “comely blonde”—that’s how reporters described her—was out and about, wearing her slacks and looking for a new place to live. She had already had run-ins with police in Maywood and Rochelle Park over her attire.

In the first week of March, she showed up in Closter to speak with a real estate agent.

“I told the real estate man my troubles at great length so he would understand, and finally he said, ‘I’ve got exactly what you need.’ Then he went to another room to telephone. We talked a while longer until he looked out the window and said: ‘Here it is now, the simple wagon for you.’ It was a police car. They held me for three hours and even called a psychiatrist, but they finally let me go,” she told a reporter.

The following day she appeared in Harrington Park, wearing a long overcoat, pants, woolen socks and sandals. Once again, people phoned the police to make complaints about what they viewed as an indecent mode of dress.

There were no charges to be filed; while Holmsen was causing a stir, she was doing nothing illegal. The best option, police decided, was to be rid of her. Officers drove her to the New Jersey side of the George Washington Bridge and put her on a city-bound bus. The consensus among all was that Holmsen’s unconventional garb would fit in better in New York City than it did in more conservative Bergen County.

“They were very nice, and even carried me in a beautiful police car to the George Washington Bridge,” she told reporters. “They didn’t deport me exactly. They just thought it would be nice if I got out of New Jersey.”

Holmsen ended up living in Flushing, Queens, on the outskirts of the 1939-1940 World’s Fair. As one news outlet put it, “The natives are all fixed to see bearded ladies, pygmy ladies and giantesses, and as a result can’t work up much interest in Ellen’s pants.”