Englewood was not yet a city, there was only the most rudimentary of police protection, and there wasn’t even a headquarters or jail cell in town. And yet, it’s where an 1873 Sing Sing prison break came to a screeching halt.

The convicts’ method of escape was like something out of a movie. Incarcerated at Sing Sing, New York’s state prison located on the eastern bank of the Hudson up in Ossining, four men serving sentences for burglary made a run for the wintry wilderness on Jan. 16, 1873.

Among the men was Andrew Riley, who had served half of his second five-year sentence for breaking into cars on the Hudson River Railroad. Daniel Bland, 20, John Marion, 19, and Charles Wilson were also in for burglary. Bland had the longest left to serve, with seven years to go on a nine-year sentence.

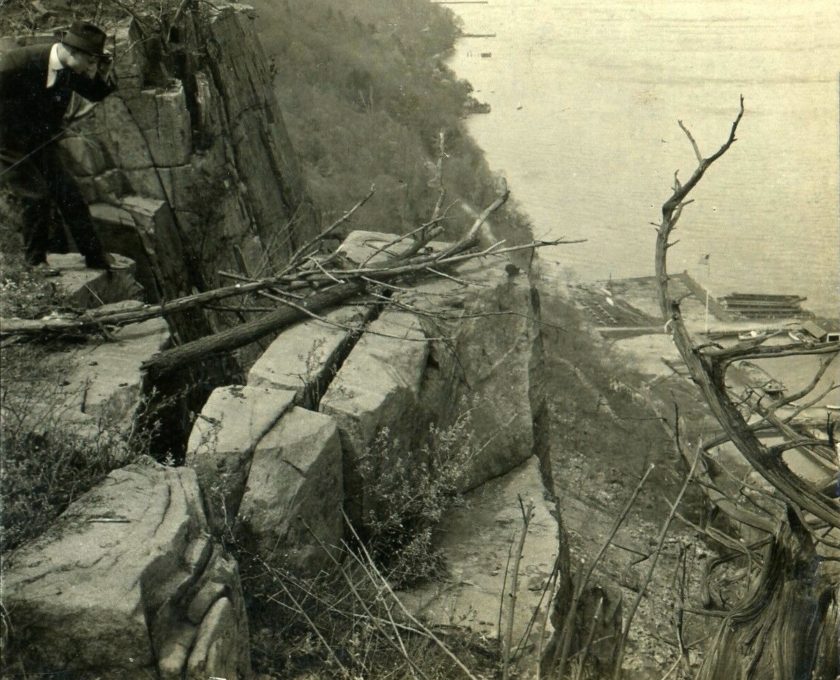

The men had been working in a shop on the prison grounds, in a building detached from the cell block. It was a particularly foggy afternoon on the Hudson River, and the river itself was frozen over for the first time in 12 years. While being marched from the shop back to the main prison building, all at once the four men ran off a dock and jumped onto the ice, starting on a full run to the opposite side of the frozen river. It would be discovered later that the men had actually put spikes on the bottom of their shoes to facilitate their sprint across the ice.

A wave of prison guards swept down toward the riverbank and shot at the fleeing prisoners, but to no avail. One bullet did go through Marion’s hat, but he was not injured. A guard was able to run down and overtake only Wilson, while the other three men escaped into the fog, across the river and into the wooded hills of the opposite shore. The prison put out an alarm to towns up and down the Hudson River.

The men were on the lam for only a single day before Marshal William Hill of the Englewood Protection Society picked them up with the help of a citizen, about a mile south of downtown Englewood.

The Poughkeepsie Eagle News printed a fascinating account from one of the men—Riley, the railroad bandit—starting with their escape across the ice.

“We ran till we were completely out of breath and could hardly put one leg before the other. At last we gained the opposite shore and climbed up the Palisades. The rocks were very slippery…We had many falls. Bland fell once about 25 feet, and would have been dashed to pieces on the ice below if it hadn’t been for a tree that grew out of the rocks. When we got to the top our hands were covered with blood. They had been torn by the ice and jagged rocks.”

The men walked south along the river, eventually entering New Jersey in what is now Alpine, but which was then part of Harrington Township.

“Seeing a light we made for the shore and found an engine house on the Jersey side, but there was no one near it. We warmed ourselves and borrowed some clothes. We then struck into the country and walked until we came to a railroad track.”

If the men followed the track, they passed through Palisade Township (modern-day Cresskill and Tenafly) into Englewood.

“After walking about four hours we came to a barn; we went in and found a sleigh, bells, and robes, but no horse. We set out again down the track, occasionally resting under the stoops of houses, in sheds and similar places. All this time the rain was pouring down and we were nearly dead with hunger.

“Early in the morning [Jan. 17] we met some railroad laborers who, supposing we were also laborers, asked us if we were out of work. We told them we were. If we had stayed with these laborers we might have escaped. After we had passed through Englewood, N.J, we were picked up by Marshal Hill, of the Protective Society—since our capture we have fed like fighters.”

The Poughkeepsie paper added, “The prisoners looked completely worn out, and gave themselves up without a struggle. They expressed great regret at coming near Englewood, and said if they could have reached Jersey City they would have been perfectly safe.”