BY KRISTIN BEUSCHER

OF NORTHERN VALLEY PRESS

ENGLEWOOD, N.J. –– With Election Day having recently passed, let’s take a look at the early days of voting in Englewood.

[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

Two centuries ago, not only was voting utterly non-private, but it was also an all-day affair.

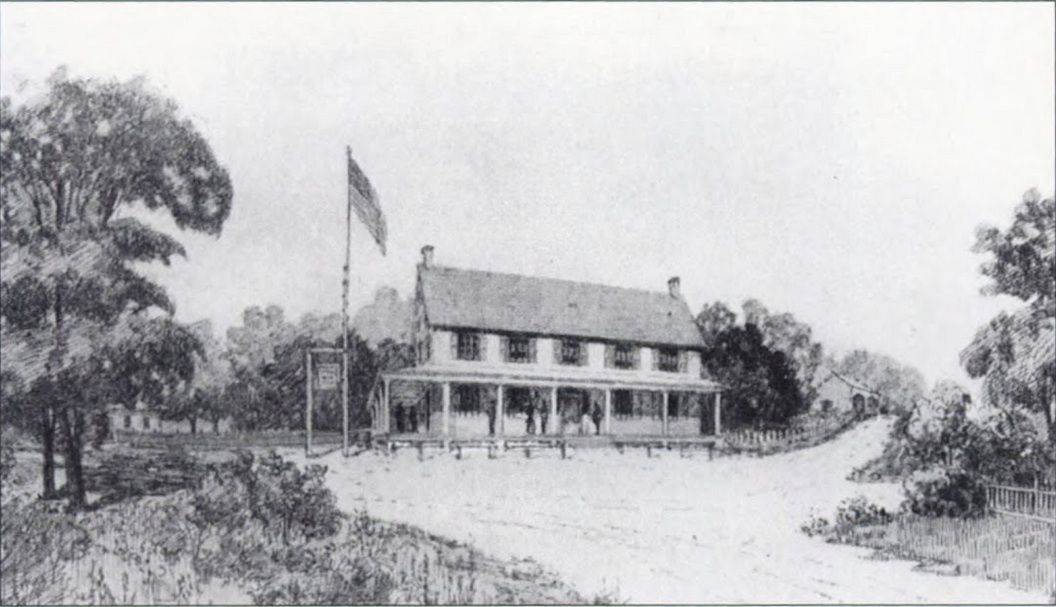

In the early- and mid-19th century, voting took place at the Liberty Pole Tavern, which was located at the junction of Palisade Avenue (then called King’s Highway), Lafayette Avenue (then known as “the road that leads to Teaneck”) and Tenafly Road.

In addition to white males, in the late 1700s and early 1800s some unmarried, land-owning women, and possibly some free black residents, would have been an active voice at the polls. That’s because New Jersey’s first state constitution, adopted in 1776, extended voting rights to unmarried women and free blacks who met certain requirements of property ownership. Married women were not allowed to vote; well into the 20th century, the husband was viewed as being the representative of the family’s voice.

By 1787 every state had rescinded the right of women to vote, except for New Jersey. However, in 1807 the state legislature followed the trend in the rest of our newly created nation, restricting the right to vote expressly to white males.

At Liberty Pole there were no ballots, and certainly no voting booths. Anonymity was not a priority. Each man spoke his choice of candidate aloud, and his preference was recorded by the inspectors “so there could be no subsequent questioning of the intention of the voter,” author Adaline Sterling wrote in her 1922 local history tome “The Book of Englewood.”

In her book she describes the phenomenon of voting at Liberty Pole, based on historical accounts.

“Election day then was, in truth, a protracted meeting, though not by reason of the size of the vote or of complications in counting the ballot,” she writes.

People had come from near and far by horseback and wagon to cast their votes, and they made a day of it.

At the time, the land that would become Englewood, Tenafly, Cresskill and Englewood Cliffs, among many others, was part of an entity called Hackensack Township, which comprised all land between New York to the north, Hudson County to the south, the Hackensack River to the west, and the Hudson River to the east. Election Day became a sort of annual reunion of residents from this neck of the woods.

“The mere act of voting did not consume much time, so there was ample opportunity to gather in groups and to discuss township affairs, crops, neighborhood news, and, perhaps, to retail a bit of social gossip until the dinner bell rang. This was a gladsome sound, for the landlord and his wife served a bounteous meal at moderate cost and there were no tiresome restrictions as to beverages accompanying the dinner.”

In the afternoon, younger men participated in outdoor sports. But, Sterling wrote, “the crowning event in which old and young participated, either as spectators or performers, was the amateur horse race on a half-mile stretch of Tenafly Road.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

It wasn’t until the 15th Amendment was passed in 1870 that black males were once again allowed to vote (although many southern states implemented obstacles like poll taxes and literacy tests to stifle participation, not to mention violent intimidation). Women didn’t gain full voting rights until the adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920, and it was decades further into the 20th century before Native Americans and people of Asian ancestry were fully enfranchised.