[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

BY KRISTIN BEUSCHER

OF NOTHERN VALLEY PRESS

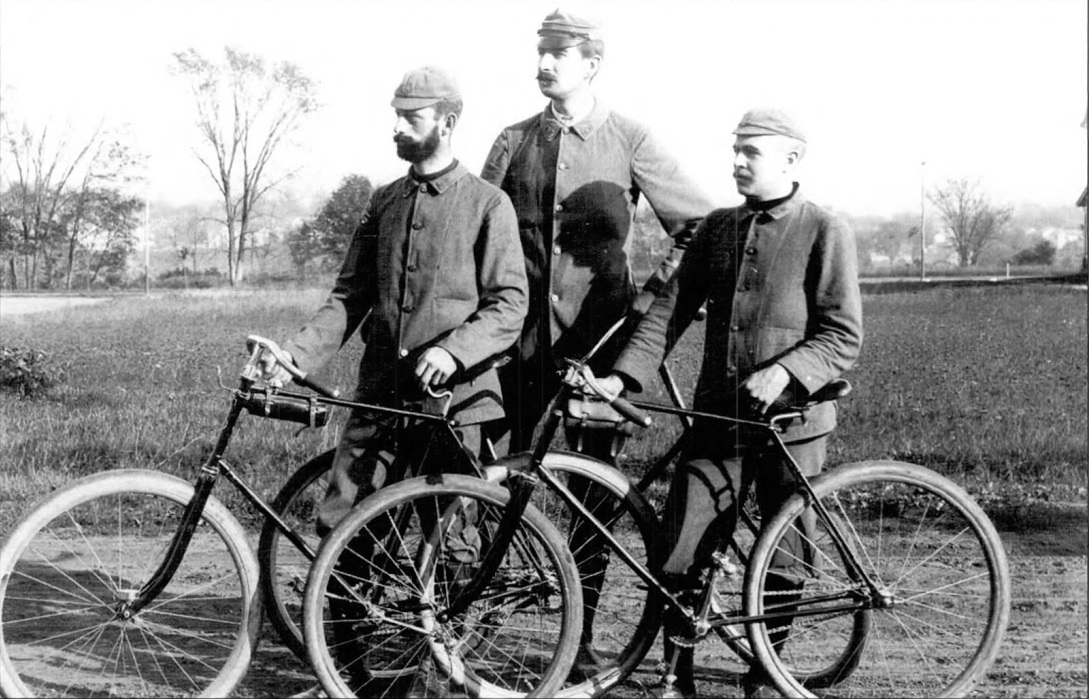

CRESSKILL,N.J.- By the mid-1890s America was fully engulfed in a bicycle craze. The high-wheeler or pennyfarthing (the 19th century bicycle with the huge front wheel and small back wheel) had been supplanted by the chain-driven “safety bicycle,” which had two wheels of the same size and looked much like our modern bicycle.

No longer limited to adventurous and athletic young men, cycling, now safer and accessible even to people in skirts, became immensely popular among men and women of all ages. So-called “wheelmen’s” clubs popped up in towns and cities all over America, as cycling enthusiasts sought to share this new hobby with others.

The New York Tribune ran a column called “News of the Cycling World,” and made mention of Cresskill in 1895.

“Autumnal charms now invite the cyclist to make tours through the country,” read the column on Sept. 12, 1895. “It is now only that the weather is more agreeable for this exercise, that the glories of the flowers and foliage of fall entice him to wander through sylvan ways.”

However, the writer offered a word of caution for any rider who might venture across the river into Cresskill.

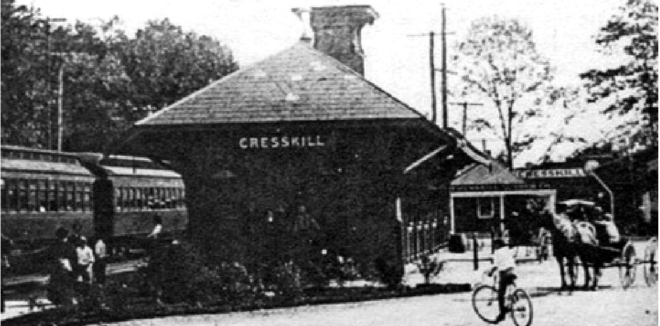

“It would be well for wheelmen who pass through Cresskill, N.J., to avoid the sidewalks as if they were pitfalls. Cresskill is a few miles beyond Englewood on the familiar road to Nyack,” the column reads.

In 1895 Cresskill was a little farming community of about 450 people. The borough was young, having broken off from Palisades Township just a year earlier.

The Cresskill Police Department was formed in 1925; before that, marshals and constables kept order in the town.

“A cyclist who last Sunday yielded to his fondness for side-path riding was promptly arrested by the town constable. After a considerable delay, he was arraigned before the local magistrate and fined $2,” the columnist explains. “The road is excellent there, and there is no real need of leaving it, but as there were no houses or people nearby, the wheelman thought it would do no harm to take the side path until he reached the village proper.”

Cresskill’s lawmen would have none of that. A constable was waiting at each end of the sidewalk to make an arrest.

“To the cyclist’s complaint that no notice of the ordinance was posted,” the columnist writes, “the magistrate replied that copies of it had been nailed to trees two or three times, but had been knocked down and carried off by indignant bicycle riders. This certainly was a short-sighted way of getting revenge on the village authorities.”