[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

BY HILLARY VIDERS

SPECIAL TO NORTHERN VALLEY PRESS

ENGLEWOOD, NEW JERSEY —— February is Black History Month, and the Englewood library has numerous events to commemorate it, including lectures and films.

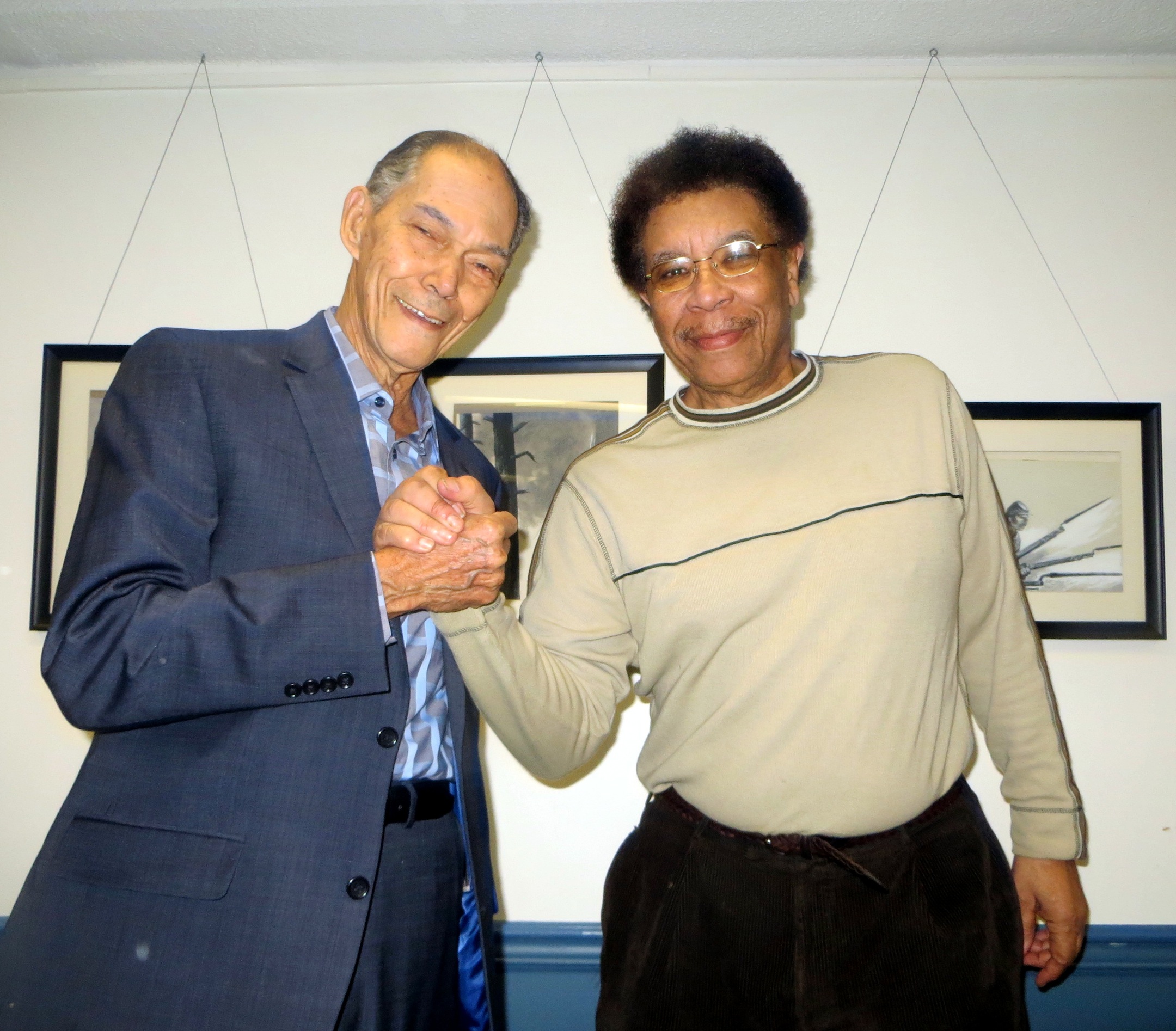

On Feb. 6, author, historian and former state Assemblyman Arnold Brown discussed the many contributions of United States Colored Troops (USCT) from Bergen County during the time of the Civil War and the crucial role that they played in the conflict.

Brown is a renowned civil rights leader. He is a past president of both the Bergen County NAACP and Urban League for Bergen County and he was instrumental in creating Englewood’s support of the African American community.

Brown, an American Democratic Party politician, became the first African American elected to represent Bergen County. Brown is also a published author. He contributed to “Past and Promise: New Jersey Women” in 1990, “Images of America: Englewood and Englewood Cliffs” in 1998 and “The Revolutionary War in Bergen County” in 2007, and he is the founder and owner of the Dubois Book Center.

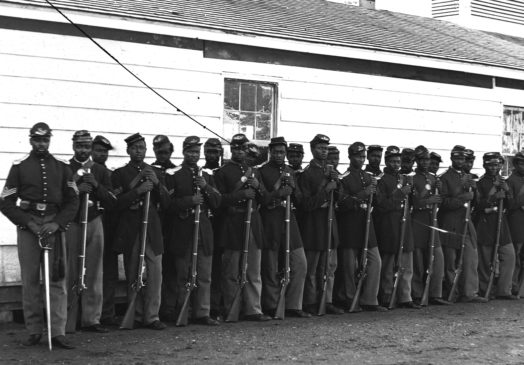

Brown’s presentation on Feb. 6, titled, “They Sacrificed to Abolish Slavery,” featured a dramatic PowerPoint show with archival photographs. Some of the rare black and white images of battle scenes came from Harper’s Weekly magazine, which launched in 1850.

A crowd of several dozen community residents that had gathered in one of the library’s meeting rooms listened as Brown conveyed a wealth of data and anecdotes about the black troops from Bergen County.

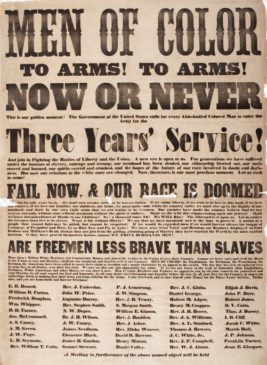

Approximately 179,000 black men—many who had formerly been slaves—volunteered to fight in the Union Army beginning in 1863 (blacks were not allowed to join the army until then even though the Civil War began in 1861). The USCT were regiments of African-American soldiers, 2,900 of whom were from New Jersey and 122 from Bergen County. The average age of the soldiers was 22. The Bergen County enlistees were farmers, laborers, porters, millers, barbers, waiters, cooks, musicians and basket weavers. Brown said that it was difficult to trace the origin of USCT soldiers because many of them enlisted in New York, which was offering a $300 bounty.

Arnold said, “I had to find the troops who were born or returned to Bergen County after the war by searching through pension files in Washington, D.C.”

By the end of the war, African-Americans accounted for 10 percent of the Union Army. They fought in many major battles, such as the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg; the Battle at New Market Heights, the Battle of Brice’s Cross Roads, the Battle of Tupelo and others. In several battles, USCT soldiers suffered heavy losses, and at some defeat sites they were lynched.

The USCT overall suffered 2,751 combat casualties during the war, and 68,178 losses from all causes. Three USCT soldiers are buried at Brookside Cemetery in Englewood.

The conditions at the battle camps were deplorable and most fatalities for all troops, both black and white, were from disease: typhoid, small pox, yellow fever, bronchitis and pneumonia.

Brown gave particular emphasis to the heroism of the USCT 22nd Regiment that was organized in January 1864 at Camp William Penn in Pennsylvania. The regiment joined the Army of the James 18th Corps near the end of that month, and was assigned to construct earthworks along the James River for protecting supply lines. In June, the 18th Corps participated in the Siege of Petersburg, for which the 22nd USCT regiment received great acclaim. They also fought in the Battle of Fair Oaks in October, where it was roundly repulsed by Confederate forces and sustained heavy losses.

During his talk, Brown explained that despite the acceptance of blacks as soldiers in the Union Army, they received significantly less pay than their white counterparts ($7 a month versus $13 a month for whites). There were also very few ranks of any importance given to black soldiers and they were never given promotions above the rank of first sergeant. However, 18 USCT troops were awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award, for service in the war.

The courage displayed by African-American troops during the Civil War played an important role in American history—it was one of the first major strides toward equal civil rights.

[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

The origin of Black History Month

A most eloquent tribute to black history was made by Brown in his presentation at the library.

Referring to a bird prized by the Akan people of Ghana, he said, “There is an African mythical bird called ‘Sankofa’ that teaches us that we must go back to our roots in order to move forward; that is, we should reach back and gather the best of what our past has to teach us, so that we can achieve our full potential. As we move forward, whatever we have lost, forgotten, forgone or been stripped of, can be reclaimed, revived, preserved and perpetuated.”

Americans have recognized black history annually since 1926, first as “Negro History Week” and later as “Black History Month.” Black History Month was initiated by Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the child of former slaves. Woodson spent his childhood working in the Kentucky coal mines and enrolled in high school at age 20. He graduated within two years and went on to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard.

Throughout his academic studies, Woodson was disturbed to find that black Americans were not represented in history books other than in inferior social positions. So, he set about writing black Americans into the nation’s history.

In 1915, he established the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now called the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History) and the following year, he founded the widely respected “Journal of Negro History.”

In 1926, Woodson launched Negro History Week as an initiative to bring national attention to the contributions of black people throughout American history. He chose the second week of February for Negro History Week because it marked the birthdays of two great leaders who championed the cause of the black American population in America: Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln.

A week becomes a month

Black History Month was first proposed in February 1969 by black educators and the Black United Students at Kent State University. The following year, 1970, the first celebration of Black History Month took place there.

Six years later, President Gerald Ford recognized Black History Month, also known as African-American History Month in America, during the celebration of the United States Bicentennial. He urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” Since that time, Black History Month has been celebrated all across the country in educational institutions, centers of black culture and community centers.

Black History Month is now an annual observance in the United States, Canada, as well as in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands (where it is celebrated as Black Achievement Month in October.)

Photos by Hillary Viders