WESTWOOD, N.J.—Pvt. Roscoe DuBois “Coach” Draper trails a lifetime of public service behind him, spreading untold lifetimes of freedom and opportunity ahead of him. The borough resident recently shared his story while a member of the U.S. Congress knelt beside him.

Then, humbly, he accepted his Congressional medal.

Draper, 100, is a former Tuskegee Airman, part of the U.S. Army Air Corps “Tuskegee Experience” that trained black pilots who served in World War II. The students flew and maintained combat aircraft at a time when the military was highly segregated.

Indeed, despite attempts to cancel the program, the Tuskegee Airmen—they were called Red Tails and Red-Tail Angels, with the motto “Spit fire”—went on to serve with some of the most highly respected fighter groups of World War II.

They escorted American bombers in raids over Europe and North Africa. Their distinguished service led to President Harry S. Truman desegregating the military.

President George W. Bush presented the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award given by Congress, to the Tuskegee Airmen as a group in 2007. Individual members are entitled to receive bronze replicas.

The original by law is on display at the Smithsonian Institution.

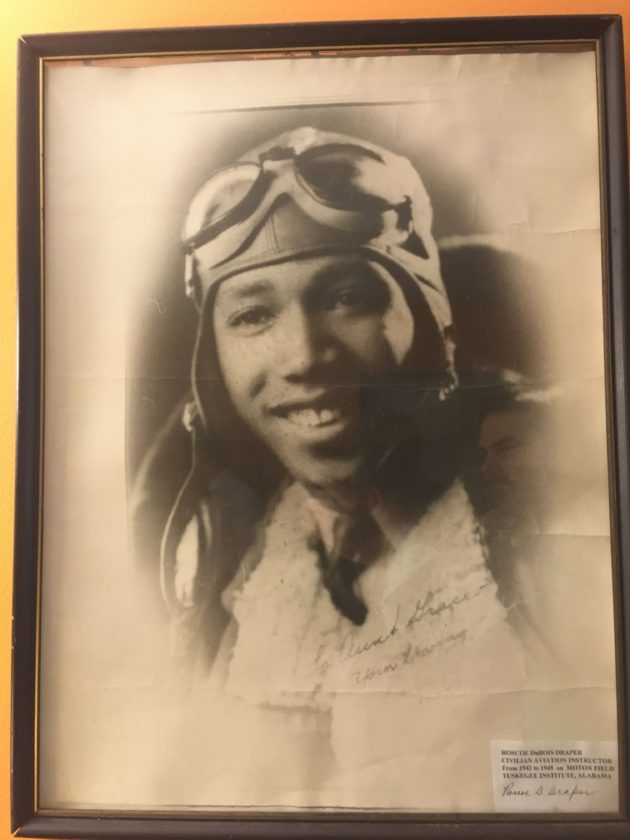

Seated beneath a portrait of himself as a dashing young pilot, and with his daughter Norma Crocker beside him, Draper on July 3 accepted his bronze medal, and a U.S. flag that had flown at the Capitol, from Gottheimer (D-5).

Draper gauged the heft of the medal, which features three Tuskegee Airmen in profile: an officer, a mechanic, and a pilot. The reverse design features the three types of planes the Tuskegee Airmen flew in World War II: the P-40, the P-51, and the B-25.

It is inscribed 2006, Act of Congress, Outstanding Combat Record, Inspired Revolutionary Reform in the Armed Forces.

Then he said, “I think it’s great. I’m honored and very grateful.”

Gottheimer said, “Pvt. Draper has lived a remarkable life and his service to our country is an example to us all. He embodies much that is great about our country. Despite facing intense discrimination, Pvt. Draper stepped up and served our country during World II, protected our democracy and freedom, and we are so much better for it.”

Throughout, Draper showed off a model Stearman Boeing PT-17 “Kaydet” biplane, which served as a military trainer in the 1930s and 1940s, and with which he is intimately familiar.

He said such a trainer is on static display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“It’s quite possible I flew that very airplane,” Draper said.

Cora Taylor, chief warrant officer in Bergen County Sheriff Anthony Cureton’s office, attended in Cureton’s absence.

She told Draper, “I’m so honored to be here and I thank you for your service—for all you’ve done—and it’s a pleasure to be here.”

Then Draper gave her a peck on the cheek—a gesture he was absolutely fine repeating for the camera crews crowded into his living room.

Also on hand was Bergen County Sheriff’s Officer Timothy O’Hare, who had helped set the wheels in motion that got Draper his medal.

When Gottheimer noted that Draper added tenures in the U.S. Postal Service and Federal Aviation Administration to his resume after the war, he said, “You have a lifetime of service and I’m expecting you to keep serving now, sir.”

Draper agreed, saying, “No big deal.”

Into the wild blue yonder

According to historian Theopolis W. Johnson, anyone—man or woman, military or civilian, black or white—who served at Tuskegee Army Air Field or in any of the programs stemming from the Tuskegee Experience from 1941 to 1949 is a documented original Tuskegee Airman.

Johnson says 2,483 persons were pilot trainees at Moton Field and Tuskegee Army Air Field (AAF) in Tuskegee, Alabama from July 19, 1941 until June 28, 1946.

On his own terms

Draper, one of the first 10 to go to Tuskegee for advanced flight training, enlisted in the Air Corps reserves as a civilian instructor in October 1942.

He was nicknamed “Chief” in honor of Arthur Anderson, Tuskegee Airmen chief flying instructor and the man regarded as the father of black aviation. He was honorably discharged in November 1945.

“I was not interested in active service,” he told Pascack Press. He explained that he’d earlier applied for active service but was denied. When African Americans finally were allowed on active duty in 1942 he declined.

“I said, ‘You wouldn’t let me in when I wanted to get in so now that you want me to get in I don’t care to be in.’ That was the way I felt about having been denied. They didn’t want me in then, so I didn’t want to be in now.”

He said he stands by his decision. He’d do it all again the same way.

“Oh yes, oh yes,” he said.

Putting the wheels in motion

For all this, Draper might not have gotten his medal but for a chance encounter.

Crocker not long ago brought her dad’s service papers to the DMV to get him an identification card. There they met O’Hare, who not only helped expedite the card but also took steps leading to Gottheimer arranging for and bestowing Draper’s Tuskegee Airmen Medal.

Crocker told Pascack Press that when O’Hare, also a veteran, saw the old-style service papers, “He got terribly excited.”

“Do you know what this is?” she said he exclaimed. She said the clerks helping her hadn’t seen that vintage before.

One hundred years young

Draper recently celebrated his 100th birthday at a party hosted by Philadelphia’s chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen. A college scholarship was presented to an aviation student as part of the festivities.

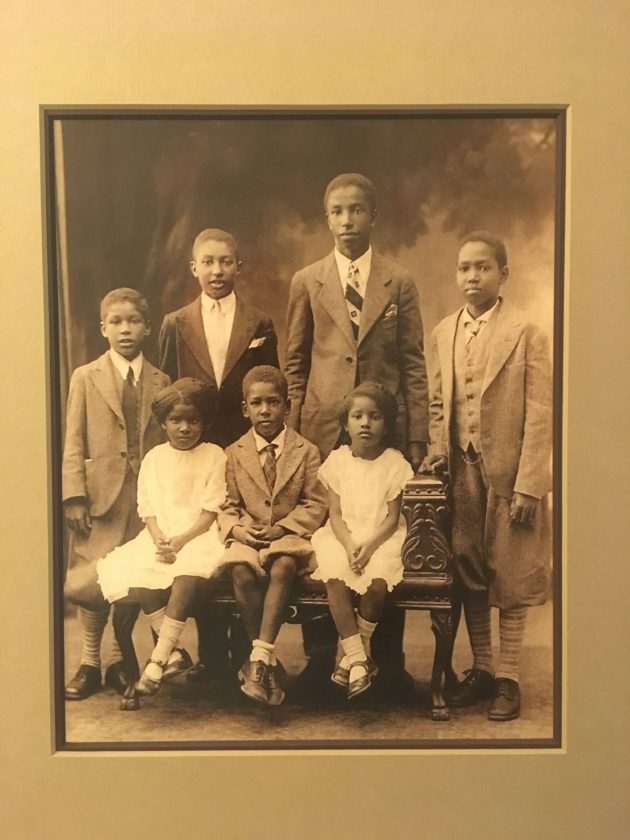

Born into a large family in 1919, he has a surviving sister, 95. He met the love of his life, Mary, in June 1944 and they were wed that November. They were together for 65 years before she passed, in 2010. He has three children in all: Crocker, another daughter, and a son.

Crocker told Pascack Press that her father is a people person lately given to describing himself as “adaptable,” as when asked his preference on what to do next.

She said that among his favorite moments is spending time with his three great-grandchildren.

— Photos by John Snyder