PASCACK VALLEY—An official from a Bergen County nature preserve told approximately a dozen residents at River Vale Public Library on May 6 that homeowners should learn to coexist with deer, take care to minimize deer impacts, and hope that the county begins a regional approach to deer management.

Merely local efforts, she said, only push the problem from one town to another.

Meanwhile, River Vale police reports we requested for 2020, 2021, and year to date show there were 82 deer–vehicle collisions on township roads — 32 in 2020 and 38, an increase of about 19%, in 2021 — leading to this year, where by press time there were 12. (Last year averaged approximately 16 such collisions through May, based on year-end totals.)

Late in 2021, a River Vale resident was killed in Teaneck on Route 4 East when his motorcycle collided with a buck on the road during early-morning hours.

We’re looking at 2022 numbers to date and will report on patterns or trends that emerge.

Fortunately, there are steps we can take throughout the Pascack Valley, even barring a comprehensive regional approach on deer population.

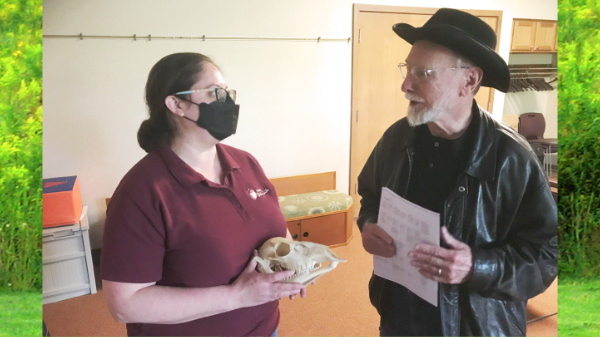

According to Tenafly Nature Center executive director Debora Davidson, speaking at a 90-minute session with Q&A on May 6 — Living With Nature: Dealing With Deer — residents should not feed wildlife, including deer, as doing so causes the animals to associate people with food.

Davidson said wildlife can find food on its own, even in winter, and should not grow dependent on handouts from humans.

Davidson described lethal and non-lethal strategies for deer management that are possible options due to Bergen County’s lack of predators for deer.

She said she believed a regional deer management approach would be best taken by the county to address a problem that spans municipal boundaries.

And she said whatever one town does to control or manage deer ultimately affects nearby towns as deer often range over a mile or more habitat to forage.

However, Davidson’s presentation offered a variety of options for individuals to deal with deer impacts, and she said everyone must choose the option that best fits their situation.

Neither Bergen County nor any regional effort is looking into deer management options.

Hunt talk paused

Over three years ago, following River Vale Mayor Glen Jasionowski’s call for a deer bow hunt in 2019 to trim the local population, River Vale’s Township Council spent eight months considering a hunt and hearing from experts on lethal and non-lethal deer management, plus residents, a majority who appeared opposed to a bow hunt, although the issue was never put to a referendum.

Officials, including the mayor, said then they preferred to make the “tough decisions” and it appeared the council favored a hunt.

However, limited public open space (e.g. River Vale Country Club), public safety concerns, not enough time to pass needed ordinances, and heated public opposition caused the mayor and council to “pause” a decision on the issue and no further action was ever taken.

In 2019, River Vale contracted for a drone aerial survey of deer that then found 96 deer per square mile, way over the 10 deer per square mile recommended carrying capacity.

Multiple public meetings held on the deer issue, and social media comments, often degenerated into highly emotional and sometimes disparaging and angry exchanges between non-lethal deer management advocates and those favoring an open-minded approach, including the possibility of a state-regulated hunt and non-lethal options.

In mid-September 2020, the council briefly discussed conducting a second deer drone survey, similar to one conducted in 2019 that found 96 deer per square mile, almost 10 times what most biologists consider sustainable.

The mayor and council took no action.

Only Saddle River in Bergen County has held a deer bow hunt, with one occurring over the last five consecutive years.

However, no action to reduce deer population has been taken by Bergen County’s other 69 municipalities.

Saddle River’s 2022 Deer Harvest Report notes, “The United Bowhunters of New Jersey thanks you for allowing us to help with your wildlife control. This season our hunters have reported pleased residents with the results referring to the reduction of deer numbers and its effect on their gardens and flower beds. I have witnessed a dramatic reduction of the browse line along the Saddle River. The low brush cover has returned making it possible to support ground nesting birds. If the deer numbers are kept within the carrying capacity of the available land, Saddle River residents will begin to see and enjoy an increase in Grouse, Quail, Snipe, Killdeer, Pheasant, Turkey, Woodcock and others again.”

Hunters saved the deer for ‘something to shoot at’

Davidson said deer were almost extinct in the early 1900s, numbering only 500,000 in the entire United States, but through conservation efforts — mostly paid for by hunters — deer were reestablished and now total almost 14 million nationwide.

She said efforts by the hunting community to reestablish the deer, “to give [them] something to shoot at” were instrumental to bringing back the deer population.

She said previously natural predators such as wolves and mountain lions kept the deer population in check, and even now coyotes may prey on weak or sick deer but not larger, healthy adult deer.

“We basically killed off in this region all their primary predators which were wolves and mountain lions. We don’t have those here, they’re gone,” she said.

She said people also “created a constant supply of food for them by bringing in plants to eat” with lush landscapes and backyard gardens.

She said more abundant food means the deer population can expand faster due to many nearby food sources, including landscapes, plants and gardens. Also, hunting is prohibited in Bergen County.

“We have, in effect, created the problem we’re frustrated with right now, which is fabulous,” Davidson said.

She said “one of our biggest problems right now has to deal with [deer] populations.” She showed a chart of deer populations, 1984–2018, numbers rising and falling due to natural population fluctuations.

Overall, however, the deer population keeps increasing, especially in Bergen County. She said now human beings are the only predator for deer in Bergen County.

She said the deer populations keep increasing, even in areas with hunting, because hunters favor taking bucks over does to get the largest rack to hang on their wall.

She said the successful return of deer nationwide was a success story “but it’s almost exceeded a little too well, super quickly.”

She said excessive deer population leads to deer browsing and less plant diversity, including increasing growth of non-native and invasive plants such as garlic mustard. She said the loss of native plants includes “pollinator plants” which affects the bee and butterfly populations, which also affects the health of other plants and natural biodiversity.

Human health impacts

Davidson described the role that deer play on health and human safety in tick-borne diseases, vehicle collisions, and agricultural property damage. She said the so-called deer tick, or tick bearing Lyme disease, actually comes from the white-footed mouse, which acts as its host, before the tick manages to climb up on a larger plant and attach itself to a deer.

She suggested people working outside “always do a tick check” and noted ticks can be anywhere, even coming out on a slightly warmer winter day. She said a lint roller rolled over clothes often removes attached ticks. She noted ticks removed within 24–36 hours usually have not yet transmitted any diseases to their recipients, unless the tick is engorged.

Collisions in focus

She said between 2010 and 2011, over 1 million deer–vehicle collisions occurred nationwide. Between 2011 and 2012, accident data showed over 31,000 deer–vehicle collisions in New Jersey.

River Vale police Capt. Chris Bulger reported 32 deer–vehicle crashes in 2020 and 38 in 2021, an almost 19% increase.

Bulger provided Pascack Press with accident reports and we will report on them in a future issue.

Davidson said due to deer numbers increasing, “it’s highly likely for you to potentially hit a deer when driving on roads.” She said human population density, deer population density, deer habitat, road size, and vehicle speeds all play a part in possibly hitting a deer.

“If you’re driving 20 to 25 miles per hour, you’re most likely not going to hit a deer. But if you’re going 60 to 70 miles per hour, you’re going to be more likely because you can’t stop in time, there’s just no way,” she said.

She said single lane, two-way roads have higher deer-vehicle collision rates but roadways with medians have lower rates because deer often stop on the median.

If an area is known for deer or signs indicate deer, take extra caution at dawn and dusk and she advised driving slower, sticking to posted speed limits, and using defensive driving techniques, she said.

She said nearly 80% of agricultural, or crop-related wildlife damage, comes from deer, including sustained crop impacts in heavily agricultural Hunterdon and Warren counties.

As for managing deer populations, she said she was “not here to say what option is the best option” but to present all the options for deer management. She said these include “lethal” and “non-lethal” strategies for deer population control.

‘Too many people here…’

She said hunting in North Jersey, specifically Bergen County, is hampered by high population density, ordinances that prohibit firearms and hunting, and lack of hunter access to properties and deer habitats.

She said Bergen County cannot be accessed for hunting “because there are too many people here…we have too many people, we have just as many deer if not more, and we can’t, we have no way of keeping their population [down].”

She said bow hunting faces strong opposition in the county.

She noted the state Department of Environmental Protection offers a manual of guidelines for how to organize and regulate a local deer bow hunt.

She said she did not favor a specific type of deer management strategy. She noted “non-lethal” strategies included chemical fertility controls, trap and relocation, fencing, deer repellents, and deer-resistant plant selections. However, most of these are not effective and deer contraception/sterilization is not a state-approved local strategy.

She said sterilization of deer with contraceptives is labor-intensive, will not lower populations for 5–10 years, is not 100% effective, and is costly. One Princeton study a decade ago showed it cost over $800 per deer to sterilize them, she said.

As for trapping and relocating deer, she said It’s only been done on a small-scale, it transports the “deer problem” from one area to another area, often spreads diseases among deer, and results in deer deaths due to problems related to transport and relocation. It also is a labor-intensive process, she said.

Other strategies include “excluding deer” from planted areas with barriers or netting, fencing, and electric fencing. All these types of deer exclusionary devices are labor-intensive too, cost-prohibitive and deer may adapt to them, she said.

She said it’s not just deer eating landscape plants, flowers, shrubs and trees, so exclusionary devices don’t always work long-term.

Other ways to prevent deer impacts on landscapes include planting deer-resistant plants, though no plant is completely deer-resistant to a hungry deer, she said.

Moreover, deer repellents such as coyote/bobcat urine, hot sauce, and putrescent eggs may work short-term but lose any repellent quality once washed off by a rainstorm, she said, and must be reapplied.

She also noted black coyote silhouettes and fake owls don’t scare off deer, geese, and other wildlife, which often habituate to them over time, finding they pose no threat.

Another deer/wildlife management strategy is to keep garbage cans sealed, said Davidson.

Davidson said “the removal of understory in forest” is one indicator of a “big issue” with deer. She said Flat Rock Brook Nature Preserve in Englewood excluded deer from a small portion of forested preserve to help restore understory.

So far, she noted Tenafly Nature Center has not had to do that as its property spans 400 preserved acres and lies adjacent to Palisades Interstate Park, while Flat Rock Brook comprises about 150 acres.

She said drone studies are also used to determine deer populations and deer range a mile or more while seeking food, shelter and mates.

One attendee at the session noted that if the public were more aware of potential negative impacts from deer, maybe something would be done. She said deer may spread disease, leave droppings, and eat landscape plants.

She said at 18 months, does generally can give birth every six months and have one to three fawns every birth cycle. She said generally deer live 12–16 years.

Asked whether there might be a regional solution for deer management, she said, “I think that’s the only way for Bergen County to take care of it is that the county take care of it. If the county made a decision and took it and people had to vote on it.”

However, she noted, even if the county wanted to address the deer problem, it would be difficult. “But I really do believe you would find a lot of obstacles, a lot of objections. You do have a lot of people who don’t want any type of lethal management to be considered,” she said, noting the public battles over New Jersey’s on-again, off-again bear hunt.

Towns took tentative action

In August 2019, Pascack Press reported that County Parks Director James Koth said county park officials would likely participate in efforts to find a regional solution to deer overpopulation problems. That year River Vale was considering a bow hunt, Englewood held a deer management forum, and many towns were advocating for a regional effort to manage deer.

No further action occurred.

Moreover, the county did not address deer management in its first-ever 2019 Bergen County Parks Master Plan that addressed issues affecting its 9,000-acre park system.

“This problem is not solved in a vacuum,” Koth said then, speaking of countywide concern about deer overpopulation. “It has to happen regionally and with lots of partners participating.”

Pascack Press emailed County Executive James Tedesco III on April 3 and 7 with ask six questions about deer management in Bergen County. We haven’t heard back.

Davidson also said the state “could override ordinances” in municipalities if a deer hunt was deemed “for the health and safety” of the public. That option is not under consideration by state officials now at any level.

She also said too often individuals think they may know more than the specialists or naturalists who deal with and study wildlife.

“We don’t know everything. I’m more than happy to listen to somebody and they might know more than I do. That’s fabulous, that’s great it means that they’ve shown an interest in learning more and educating themselves,” Davidson said.

She provided a list of native, deer-resistant plants compiled by Cornell Cooperative Extension of Ithaca, N.Y in 2021. The list includes herbaceous plants, vines, grasses and sedges, ferns, shrubs and trees, plus a description of six deer repellents.