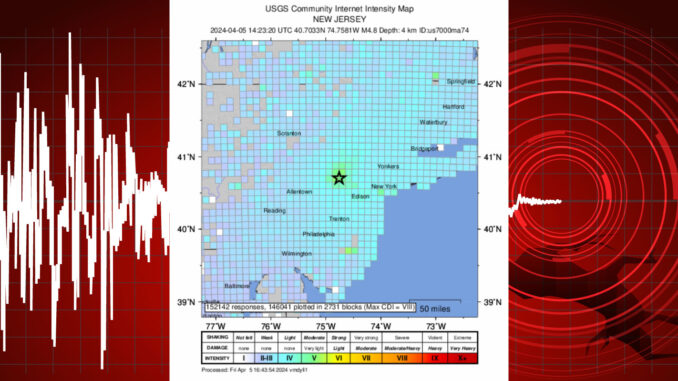

PASCACK VALLEY—Be ready for more rock and roll. According to the United States Geological Survey’s Earthquake Hazards Program, the 4.8-scale earthquake that rattled the East Coast Friday at 10:23 a.m., centered on Lebanon, N.J., can spawn aftershocks.

In that event, “Drop, Cover, and Hold on. More earthquakes than usual (called aftershocks) continue to occur near the mainshock. The mainshock is the largest earthquake in a sequence (a series of earthquakes related to each other). When there are more earthquakes, the chance of a large earthquake is greater which means that the chance of damage is greater,” says the USGS.

It adds, “No one can predict the exact time or place of any earthquake, including aftershocks. Our aftershock forecasts give us an understanding of the chances of having more earthquakes within a given time period in the affected area.”

And it says the chance of at least one aftershock within the next week is 45%.

Friday morning’s quake was felt up and down the state, and in New York City and much further afield—even into New England—according to the USGS and check-ins with family and friends.

“Our region just experienced an earthquake with a preliminary magnitude of 4.7, with an epicenter near Readington in Hunterdon County. We have activated our State Emergency Operations Center. Please do not call 911 unless you have an actual emergency,” Gov. Phil Murphy said on social media in the immediate wake of the event.

News reports said New Jersey Transit announced its rail service was subject to up to 20-minute delays in both directions due to bridge inspections, the Holland Tunnel was delayed for inspection, and Newark Liberty International Airport ordered a ground stop following the quake.

In the immediate aftermath of the quake, Westwood architect William J. Martin tweeted, “I immediately knew it was an earthquake. It felt like a 4ish in magnitude. I’ve been in four earthquakes including this one. Building damage starts around magnitude 6. Reports are 4.7. Everyone check your buildings for cracked wallboard or foundations.”

Martin told Pascack Press at 1 p.m. that although the East Coast is less prone to quakes than the more geologically active West Coast, the New York City area is “overdue for a 6-point quake. We get them every 150 years or so. And if that happens, that much energy released, that could be a problem, especially for brownstones—four, five, or six stories—because they’re made of non-reinforced masonry.”

Martin is chairman of the Westwood Zoning Board of Adjustment and member of the Westwood Planning Board, and serves on the Bergen County Historic Preservation Advisory Board.

Here are the mechanics of an earthquake:

- Faults and Stuck Edges: Faults are fractures in the Earth’s crust where blocks of rock move past each other. At times, the edges of these blocks are stuck together due to friction.

- Energy Accumulation: As the tectonic plates continue to move, the stuck edges accumulate energy. This energy is stored in the rocks along the fault line.

- Release of Stored Energy: Eventually, the force of the moving blocks overcomes the friction of the stuck edges, causing them to “unstick.” When this happens, all the stored-up energy is suddenly released.

- Propagation of Seismic Waves: The released energy spreads outward from the fault in all directions. This energy travels in the form of seismic waves, similar to ripples on a pond when a stone is thrown into it.

- Shaking the Earth: As these seismic waves move through the Earth, they cause the ground to shake. This shaking is what we perceive as an earthquake. When the seismic waves reach the Earth’s surface, they shake the ground and anything on it, including buildings, infrastructure, and people.

Martin said the shallowness of the hypocenter—the actual point within the Earth where an earthquake originates—relative to the surface of the Earth meant this quake produced more side-to-side motion. Deeper tectonic plate collisions produce more up-and-down waves. (The epicenter is the point on the Earth’s surface directly above the hypocenter. It is the point on the ground where the seismic waves are first felt and where the earthquake’s effects, such as shaking, are typically the strongest.)