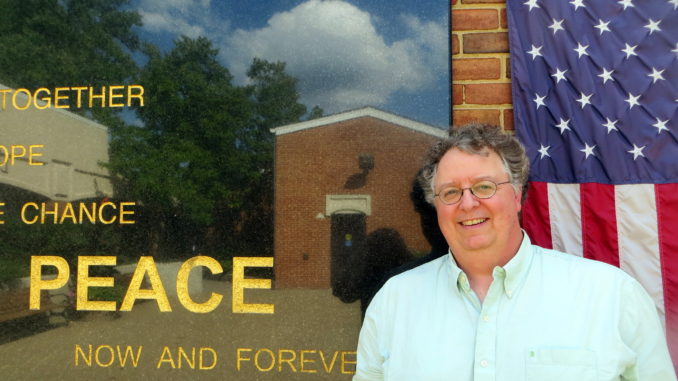

TENAFLY, N.J.—Tenafly resident Thorin Tritter, Ph.D., recently joined the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Nassau County in Glen Cove, N.Y., as museum and program director and his job is one of great importance.

“The mission of the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Nassau County, founded in 1989, is to teach the history of the Holocaust and its lessons through education and community outreach,” Tritter explained. “We teach about the dangers of anti-Semitism, racism, bullying and all other manifestations of intolerance. We promote resistance to prejudice and advocate respect for every human being.”

To do this, the center presents a detailed and comprehensive chronicle of the Holocaust, and utilizes multimedia displays, artifacts, archival footage, testimonies from local Survivors and Liberators, and encompasses a special gallery for changing.

It offers a contextualized history to explain the 1930s increase of intolerance, the reduction of human rights, and the lack of intervention that enabled the persecution and mass murder of millions of Jews and others, including people with disabilities, Roma and Sinti (Gypsies), Jehovah’s Witnesses, gays, and Polish intelligentsia.

The center, recommended for ages 10 and older, introduces visitors to European antecedents which nurtured the evolution of Nazism, such as centuries of anti-Semitism and racism, the pseudo-science of eugenics, and the repercussions of World War I.

A wealth of experience

Tritter brings a wealth of experience to his new position. Born in England, Tritter moved to the United States in 1972. He received his B.A. in American history from the University of Chicago and an M.A. and Ph.D. in American history from Columbia University.

Tritter taught American history and American studies at Princeton for six years and then served as a Research Fellow at the University of London. From 2003-2011, he served as the director of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History’s History Scholars Program.

For the past seven years, Tritter has served as the executive director of the Fellowships at Auschwitz for the Study of Professional Ethics, an independent nonprofit that takes graduate students in professional degree programs to Germany and Poland, where they use the actions of Germans in their particular profession during the Holocaust as a launching point for an intensive course of study on contemporary professional ethics.

“Auschwitz is more popular than ever, with over 2 million visitors a year,” Tritter said. “Many people are fascinated by evil as well as by the desire to understand history.”

As museum and program director, Tritter oversees the upgrading and curation of the center’s permanent and special exhibitions and is responsible for continuing its topical and impactful community programs open to the public.

Besides portraying the broad picture of life in Nazi Germany, the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center has many small and intimate exhibits that are both thought provoking and heart wrenching. One example is an accordion that belonged to Alex Rosner, a survivor of Auschwitz. Rosner was born in Poland to a musical family, with a father, Henry Rosner, who was a famous violinist.

When Rosner and his father were deported to Auschwitz, someone recognized Rosner’s father and asked him if he played. When he said he played the accordion, someone brought one from the warehouse of confiscated goods so that he could accompany his father. While his own musical abilities were part of how he survived, Rosner readily admits that far more important was his father, who when asked to perform for the commandant, said he would perform only if his son would be saved.

Later Rosner and his father met Oskar Schindler, who eventually put them on his “list” and helped them to survive at Auschwitz.

In 1945, both Rosner and his father were sent on a death march to Dachau, but managed to survive, and were liberated by the American forces and moved to the United States.

Schindler recovered Rosner’s accordion from Auschwitz and returned it to the Rosner family, who donated it to the Holocaust Center. His father’s violin is in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

“In addition to Rosner, we have worked with over 40 or 50 other Holocaust survivors,” Tritter recalls. “Our museum was actually begun by a group of survivors who would meet with student groups and the public.”

Another noteworthy item on display is a German beer stein decorated with anti-Semitic caricatures. It shows the openness and complicity of the general public’s disdain for Jews.

The Holocaust exhibition concludes with the aftermath of Nazism and emphasizes the issues of displaced persons camps, emigration, and post-genocide justice.

“One feature that distinguishes our museum from other Holocaust museums is that we demonstrate the relevance of the Holocaust in modern times through our examination of current genocides and intolerance and by the celebration of today’s genocide rescuers and Upstanders,” Tritter said.

“We have an obligation to teach young generations the lessons of the Holocaust. The Holocaust did not end in 1945. We need to hear the stories and speak out against anti-immigrant and anti-Semitism in the U.S., the anti-Muslim cleansing in Kashmir, the genocide in Myanmar and many other hateful events around the world,” said Tritter. “At our museum, we even had survivors of the genocide in Rwanda tell their stories, including a woman who was raped at age 14 and her family was slaughtered.

“We need people to hear these horrific stories from the past so that they will stand up against injustice now and in the future,” Tritter said. “We can’t all be Martin Luther King, but we can all act on a smaller level.”