Pascack Press reported May 3 on the May 20 archaeological dig in Park Ridge, which revolves around the region’s once prevalent wampum-making industry.

Researcher Eric Johnson, a Ph.D. candidate with the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University, hopes to find shards and pieces of shells from the Campbell family’s first wampum production mill in an area of Silver Lake park.

Today we delve deeper into an industry that has led history scholars from all over the world to our little corner of the Pascack Valley.

The story begins when John W. Campbell (1747–1826) of Closter moved with his wife Letitia Van Valen to a farm they purchased on Kinderkamack Road North in Montvale, close to the New York state border. John W., like many farmers of his day, found a second job during the long winter months. He chose to create wampum, beads made out of clam shells, that the Indians used for gifts and personal adornment.

Indians had traded among themselves with wampum prior to the arrival of European settlers, but creating it—by essentially boring into hard pieces of shell—was a slow task. Dutch settlers joined in the production of wampum as a means of trading with the Indians. For the settlers, wampum was a seasonal craft, mostly done October–April during downtime on the farm. By the mid 19th century the production of wampum was regarded as among the more important industries Bergen County, and Park Ridge’s Campbells were at the forefront. John W. Campbell is credited with inventing the shell “hair pipe” wampum made from Caribbean queen conch shells that came as ballast on trade ships heading for New York City.

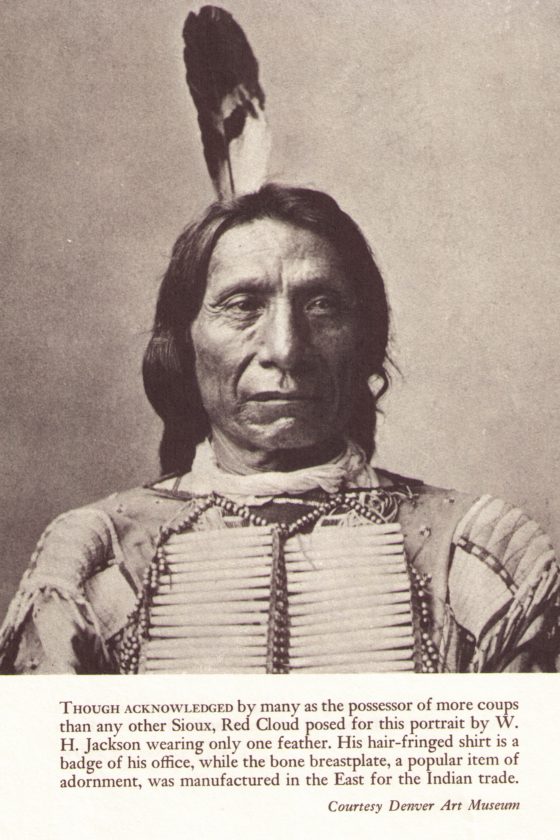

These tubular beads can be seen in early photographs on the breastplates of Indian warriors. The shell hair pipes put the Campbells on the map. Lewis and Clark bought and took Campbell hair pipes on their famous westward expedition in 1804.

In 1808, John W.’s son Abraham (1782–1847) moved to Main Street (Pascack Road) in Park Ridge, where he opened a blacksmith shop and wampum bead business. Abraham’s sons John A., James A., David A. and Abraham Jr. eventually became partners in the blacksmithing business and built a new mill along the Pascack Brook near the bottom of Wampum Road.

In the mid-1800s the Campbells revolutionized wampum production by inventing a hydraulic drilling machine that streamlined the production process. The hand-made wooden machine enabled multiple hair pipes to be drilled at one time, uniformly, and with minimal breakage. More than one drilling machine existed, but today the only remaining example is housed at the Pascack Historical Society’s John C. Storms Museum, 19 Ridge Ave., Park Ridge. The Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C. has asked to acquire the machine for its collection, but for the time being it will stay where it was invented—in Park Ridge.

The Campbells did not sell their hair pipes directly to the Indians. Rather, they sold them wholesale to New York merchants, such as John Jacob Astor, who resold them to firms of Indian traders in the United States and Canada and to the United States government.

Today the wampum-making industry that existed locally is a cornerstone of the Pascack Historical Society’s museum, where one can find information about the Campbell family and their wampum mill, early wampum-making tools, and even the Campbell family’s business ledgers, which offer a precious glimpse into life in the Pascack Valley in the 19th century, and the families who lived here.

As the repository for all things wampum in the Pascack Valley, the museum, housed in an 1873 former Congregational Church, has been sought out by scholars from across the world.

Last year the Pascack Historical Society heard from Johnson and collaborated with him as he conducted research for his doctoral dissertation. His paper concerns wampum production and its role in economic interdependence between production and consumption between 1750–1900. (Intrepid PHS Trustee Dr. Marilyn Miller, of Park Ridge, even ventured into the weeds off the Pascack Brook with Johnson as he searched for the former footprint of the wampum mill.)

As Johnson’s archaeological dig kicks off on Monday, it remains to be seen how the story of Pascack Valley wampum will continue to evolve.

The public is welcome to drop by the dig site to ask questions. Johnson said he would be interested to talk to any residents who have found seashell fragments while digging in local yards or gardens or people whose ancestors worked in the wampum trade.

For more on the Pascack Historical Society, call (201) 573-0307 or visit pascackhistoricalsociety.org.