TOWNSHIP OF WASHINGTON—Who remembers Washington Township’s Fair Play Club? Maybe you were a member of this club as a youngster, or you had a brother who was.

Ridgewood Road resident Edward Barber single-handedly started the Fair Play Club in 1963 after some older bullies had jumped his 10-year-old son and two other neighborhood boys. Barber set out to teach his son and friends the art of self-defense and help them build muscle, all while giving lessons on some rules and regulations of fair play.

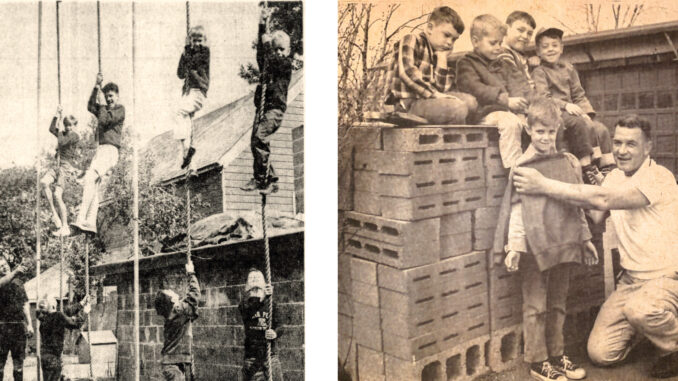

The boys invited their friends, who invited their friends, and so on. Within a few years the club that started with just three kids had grown to include more than 200 local boys, ages 5 through 15, who were meeting Saturday mornings on Barber’s 2-acre property to learn about physical fitness and sportsmanship. All through the warm months they climbed ropes, had boxing matches, did push-ups and chin-ups, played basketball, and lifted weights. The members were given matching shirts with the club logo (depicting a handshake) and they marched in the Memorial Day parade with a Fair Play Club banner.

In addition to a bevy of athletic equipment that he had paid for and built with his own two hands, Barber’s property was a fun atmosphere for the boys, with a barn, horses, and three dogs running around. The Fair Play Club, for the many hours it involved, was a volunteer role. In his professional life Barber ran the Township Fuel Oil Co., a delivery service for oil heat customers.

The rugged 6-foot-tall, 215-pound Barber, whom the boys affectionately called “Uncle Ed,” had served as a paratrooper during World War II and placed a high value on physical fitness. When the boys asked if he could climb the 20-foot rope, Barber was a good sport and fought his way to the top.

“I can’t expect them to do things that I can’t do,” he told a reporter back in August of 1967.

In a club of over 200 boys, there were bound to be conflicts. However, Barber’s verbal ban on fighting (expect for friendly matchups in the boxing ring) was dutifully heeded—a testament to how much the kids looked up to him. He believed that a key to keeping young people out of trouble was giving them a worthwhile alternative.

For his efforts, the township gave him an award for helping to keep the juvenile delinquency rate low.

“We teach self-defense,” Barber explained to a reporter in 1969, by which time the group had grown to include 250 boys. “We also stress that a boy should not go looking for a fight, but if one is pressed on him, he should have the physical stamina, know-how, and courage to face it. That is the basic tenet of this group.”

He added, “If our program reaches three out of 10 boys, we feel it is successful. In fact, if only one boy gets a lot out of the program, we are contented.”

Barber also dispensed life advice, telling the boys to avoid hitchhiking and to keep their hair cut short and tidy (this was, after all, the late 1960s).

“I tell them they can have long hair if their fathers have long hair, and I know most of their fathers—they don’t have long hair,” Barber said in 1967.

In April of 1966, as the club was taking enrollment for the coming season, an article appeared in the Park Ridge Local newspaper that showed just how enthusiastic the boys were: “All members are requested not to get to classes before 10 a.m. please, please, please! Some have been arriving 15 or 30 minutes ahead of time and if it keeps up that way, they’ll start camping on the doorstep the night before.”

As the club grew, it evolved to include a formal registration process and a crew of parent volunteers. Held every summer, the seasonal program would end with the awarding of trophies in various categories for the boys who had made the most progress, as well as a big family picnic.

After the 1970 season, Barber left the township. He moved to upstate New York with the goal of starting a boys’ summer camp on a 150-acre property he had bought near Cooperstown. With help from the township’s Contemporary Woman’s Club, which took on the Fair Play Club as a fundraising project, parent volunteers kept the program going into the 1970s, but it eventually disbanded.

— Kristin Beuscher is president of Pascack Historical Society.