WESTWOOD—After 50 years, Lee and Annie Tremble are turning over the Iron Horse restaurant to a new owner. It opens a new chapter for them, as well as in the history of the iconic Westwood eatery.

Inside the Iron Horse, the walls are decked out in railroad memorabilia. Lanterns, model trains, signs, old photographs, and railway prints adorn walls and shelves, creating a miniature museum that entices history buffs and keeps dinner conversation flowing.

Even the restaurant’s name is a reference to an early term for locomotives. It is a fitting theme for an establishment located a stone’s throw from the railroad tracks.

Yet, this place and its connection to the railroad goes much deeper than proximity. Its history stretches back nearly 150 years to an era when Westwood was a rural hamlet that city folks would visit for country vacations. In the years since, it has been a steady part of the streetscape as the march of time transformed the borough.

The story begins in the 1870s, a time when all of our present-day Pascack Valley towns were country villages within one massive Township of Washington. The region had always been relatively sheltered from the outside world, and the few people who lived here were mostly farmers and tradesmen whose families lived on the same land for generations. Tremendous swaths of field and forest covered the landscape, cut by babbling brooks and dirt lanes. Then, as now, the East Coast’s hub of commerce was New York City—and getting there required hours of being jostled in a stagecoach.

In 1870, the Hackensack & New York Extension Railroad expanded its rail line into the Pascack Valley. This lifeline for communication and transportation put the region on a completely different trajectory. A trip to New York City was reduced to just an hour by rail and ferry, and it became possible to live in the country and commute into the city. Developers quickly caught on to the real estate potential of this pristine landscape.

Those real estate prospects brought many visitors to the Pascack Valley as people came to look at properties for full-time residences and summer homes. The area also became a vacation destination in the warm months, with many New Yorkers fleeing the stifling city to spend a few breezy days in our bucolic valley.

Salesmen traveled the rails and visited general stores up and down the tracks. In the 1870s, hotels were built next to nearly every station on the line and did a good business providing hospitality for the out-of-towners.

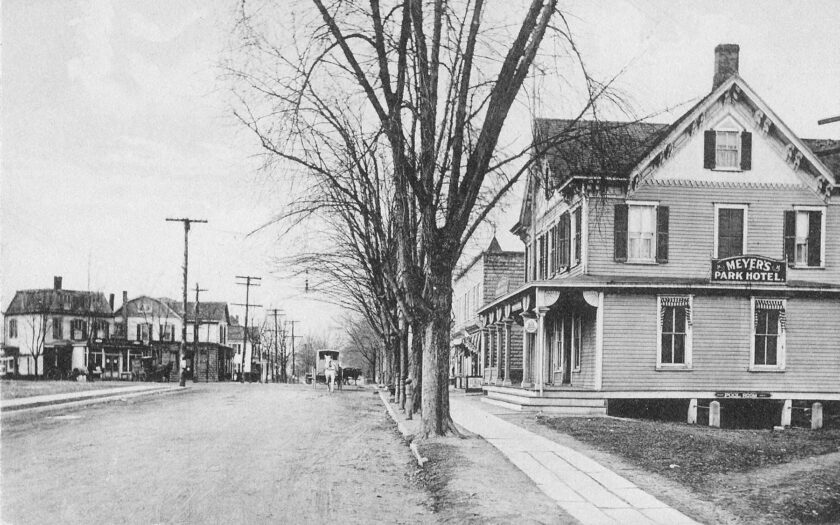

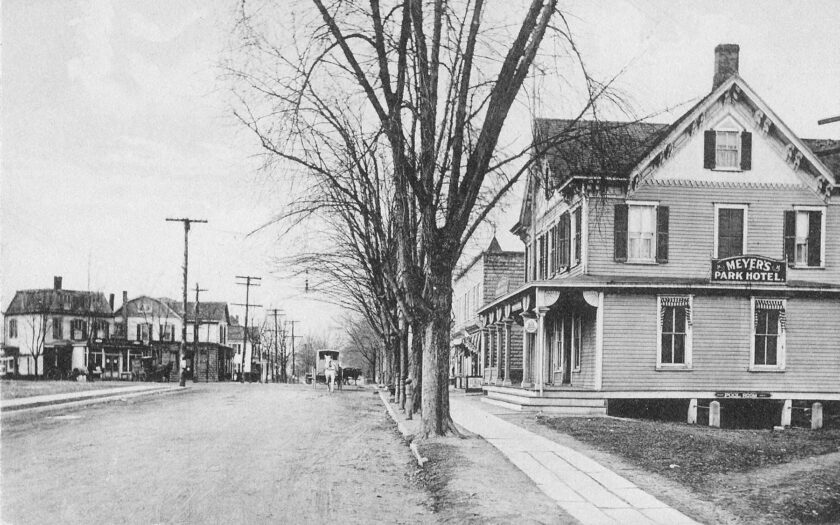

In Westwood, a new hotel went up in 1877 beside the tracks at what is now Washington Avenue and Broadway. The clapboard-sided building with its long front porch, gabled roof, and elongated windows was called the Park Hotel. In the 19th century several different proprietors added their names above the door: C.S. De Baun, Adam Collignon, and then Christian Huber at the turn of the century.

However, most of the photographs we have are from the era when it was Meyer’s Park Hotel, under the ownership of German immigrant Ernst Meyer, who bought the place around 1910.

Meyer made many changes to the building. He enclosed the porch surrounding the hotel and leased parts of the first floor to other businesses—real estate agents, florists, a tire dealer, a butcher. The family lived on the second floor, while the third floor had hotel rooms. The inn had one of the first telephones in Westwood.

The Park Hotel had been a saloon for decades before Prohibition took effect in 1920. Meyer apparently continued serving, although he did it on the quiet. A news report from February 1931 describes how county detectives raided his speakeasy and seized a large quantity of liquor. Meyer and the barkeep were arrested.

The place was a gin mill known as the Park Tavern when Lee Tremble’s parents, Marion and Dudley, bought the bar along with friend William Noonan in 1972. Dudley was a vice president of the Coca Cola Co. and Marion was an active community volunteer in Westwood. Noonan was a sales manager in a pharmaceutical company. They ventured into the restaurant business with a $45,000 investment. Dudley managed the books and Marion designed the menu with what would come to be iconic dishes at the restaurant, such as hamburgers with a hidden pocket of cheese and railroad tie fries. Noonan was the jack of all trades. The Trembles brought their then 21-year-old son, Lee, into the business.

They kept the bar but expanded the dining room and also gave the restaurant a new name—the Iron Horse. On opening night, a line formed outside the door. The place was a hit—and, in an amazing feat in a notoriously difficult industry, the Iron Horse remains a local favorite after more than 50 years.The scene March 21, 2022: Coffee and a fantastic birthday cake were served from 11 a.m. to noon, and the restaurant and bar — closed Mondays as a concession to staffing shortages stemming from the pandemic — opened its kitchen and bar at 4 p.m., delighting throngs of 50th-anniversary revelers.