BY MICHAEL OLOHAN

OF NORTHERN VALLEY PRESS

NORTHERN VALLEY AREA, N.J.—A state lobbyist representing New Jersey’s 565 municipalities told approximately two dozen Bergen County mayors on April 9 that tax revenues from hosting a marijuana business would go to the local treasury and not to Trenton.

State League of Municipalities Deputy Executive Director Michael Cerra said if a municipality opts to host a hypothetical marijuana enterprise—whether it’s a retail, cultivation, distribution or wholesale business—the tax revenues go directly to the municipality.

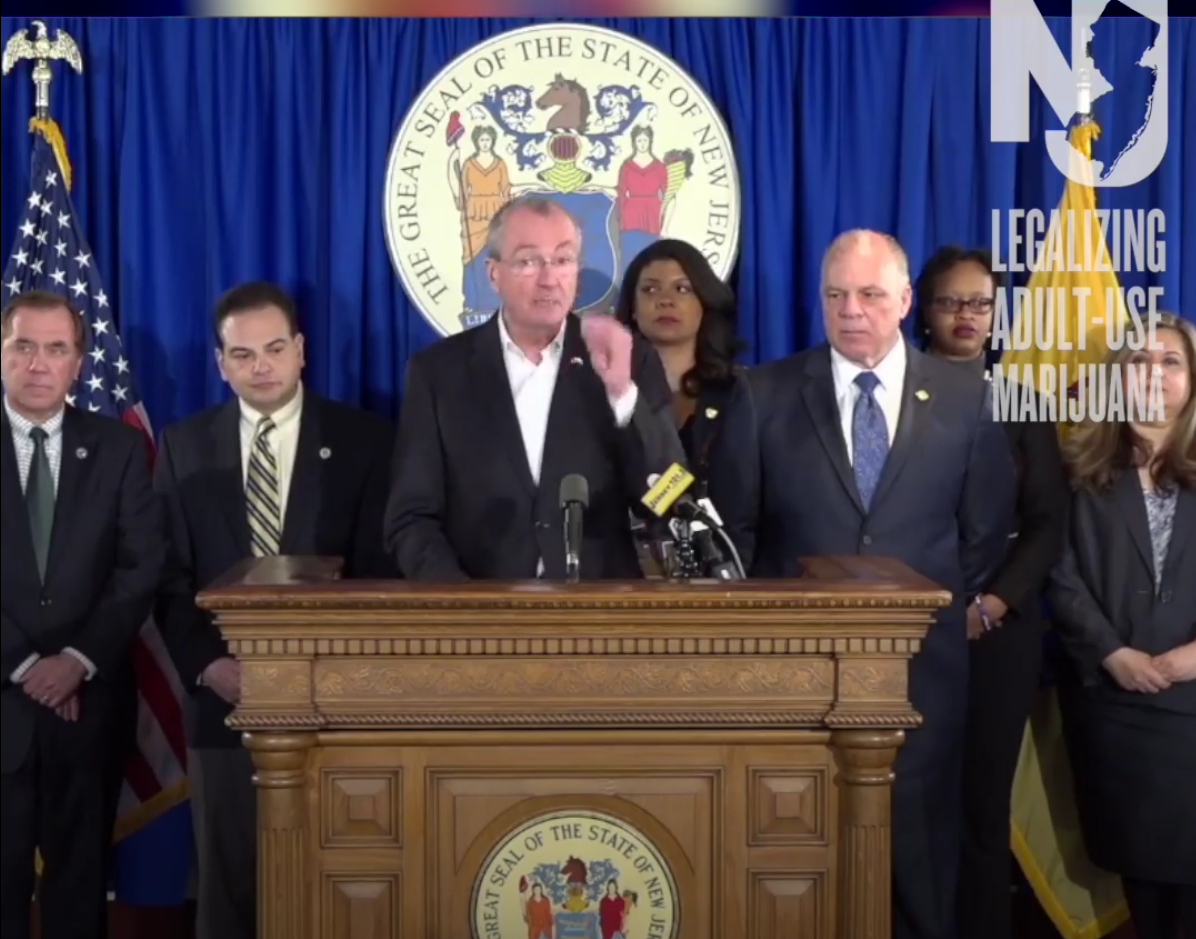

In March, state lawmakers canceled a vote on a bill to legalize marijuana for adults after supporters failed to line up enough support. Legalizing marijuana was a campaign promise of Democractic Gov. Phil Murphy, who eyes it in part as a significant revenue stream.

Speaking at a breakfast meeting of mayors from Bergen County’s League of Municipalities at Coach House Diner in Hackensack, Cera addressed cannabis legalization and affordable housing, and answered mayors’ questions.

The league has taken no formal position on legalization, he said. It’s followed the legislation, offered regular online updates, and is holding three roundtables to answer questions on both cannabis and affordable housing, he said.

Towns must decide if legalization bill is approved

Cerra said if and when marijuana is legalized—which may happen in May or later this year—the current 175-page bill includes a 3 percent local tax on gross revenues; 2 percent local tax on cultivation and distribution businesses and one percent on wholesale enterprises.

He said local sales tax revenues would be paid directly to a local chief financial officer.

Cerra said if the bill passes, municipalities must decide whether to opt in or out on hosting a marijuana establishment.

If no decision is made, a cannabis entity is considered a conditional use in a commercial or retail zone, subject to local zoning code.

Without a decision in 180 days, the town must wait five years until it can opt-out of any cannabis license, with existing license holders grandfathered, he said.

“You can opt in for one or all four types of licenses. The issue is you have to do something within 180 days,” said Cerra.

Cerra said the legalization law allows local zoning and laws to control if and where a cannabis facility is located.

Cerra said there were at least three or four Democratic Senate votes opposed to legalization, which caused Democratic Assembly and Senate leaders to call off the March 25 vote on legalization.

Cerra said because the bill is included as a package with a bill to expand medical marijuana and an expungement bill, the lack of support delayed those efforts, which had more support than the legalization bill.

When Cerra spoke about some towns’ interest in hosting such a facility, Bergen County League of Municipalities President Paul Tomasko, mayor of Alpine, informally polled mayors from about one-third of Bergen County at the mayors’ breakfast to see what towns planned to host a cannabis facility.

Not one mayor supported adult-use marijuana sales but at least a couple mayors supported a medical marijuana dispensary.

Cerra told the mayors he anticipated some towns statewide will hold non-binding referendums this year to get feedback from residents on whether to allow a cannabis enterprise.

Englewood Mayor Michael Wildes asked if it was “wise” to offer such a ballot question and Cerra said such a referendum provides feedback, political cover, and a reading on public sentiment.

Wildes also said he did not believe enough information on legalization was being shared with local officials, which Cerra said was part of their rationale for holding forums on the topic statewide.

Cerra said he anticipates most towns statewide will opt out initially, but wait until the industry “matures” and possibly opt in later if it makes sense.

If the legalization bill is eventually approved, Cerra said towns may be more open to non-retail operation, such as a cultivation facility, once towns have had time to evaluate the opportunity.

Cerra said an existing ordinance banning certain types of cannabis enterprises must be revised to meet the new law. He said the League will offer draft language for ordinances to enable a municipality to opt in or out of four cannabis businesses.

“Obviously there’s a strong opposition to this,” Cerra said. “We’ve also heard from other towns that are very interested.”

Legal marijuana’s ‘effects’ unknown

Hillsdale Mayor John Ruocco said he had not seen much research on effects of legalization in Colorado, or impartial scientific evidence on marijuana, and Cerra said that there may not be, as most lobbyists and organizations are working “angles” to either promote or prohibit cannabis.

“I get emails from people against it and calls from people who want to start it in my town,” Ruocco said, questioning Cerra on impartial data on cannabis.

Cerra said he could not speak to whether marijuana was a gateway drug or its scientific benefits.

He said Murphy included an estimated $60 million in state sales tax revenues from legalization in his proposed state budget.

Cerra addresses affordable housing

Cerra said the Superior Courts cannot continue to administer affordable housing obligations, calling the current system with courts and Fair Share Housing Center a “dysfunctional, chaotic process” with different applications of law in every county.

The state Supreme Court ruled that superior courts would determine affordable housing obligations in 2015, after it declared the Council On Affordable Housing ineffective due to a 16-year period marked by court fights over housing formulas and political inaction.

COAH was the administrative agency created under the state’s 1985 Fair Housing Act to administer fair share obligations required of municipalities under the Mount Laurel decisions.

He said the Supreme Court decision requiring affordable obligations for a 16-year “gap period” 1999–2015 when the Council on Affordable Housing did not operate effectively, also hurt towns.

Cerra called for an administrative process—not the courts—to administer the affordable housing law.

He said he’s hoping legislative efforts will allow a community to transfer part of its moderate housing obligations for “workforce housing” in another community.

He said “this wouldn’t have the baggage” that Regional Contribution Agreements (RCA) had, which were disallowed in 2008 by the state Supreme Court for “concentrating poverty.”

Cerra said that “workforce housing” would comprise 80 percent to 100 percent of median income as determined in each of the state’s six affordable housing regions. He said the legislation is sponsored in the Assembly by two Democrats representing parts of Somerset and Mercer counties.

“I never thought we’d see the day when some of us, at least, would come to miss COAH,” Tomasko said.

Among meeting attendees were Old Tappan’s John Kramer, Closter’s John Glidden, Harrington Park’s Paul Hoelscher, Tenafly’s Peter Rustin, and Montvale’s Michael Ghassali.