WESTWOOD, N.J.—His name is Mark, and he made the news when on Valentine’s Day 2014 one of many bags of heroin he brought to his girlfriend’s house fell on the floor, and was picked up by her 9-month-old son.

—Who sucked on the bag, and overdosed, quickly becoming unresponsive.

Mark called his younger brother, Craig, desperate for help, and Craig—an addict as well, who had been sober for nine months at the time—refused.

Craig—who’d progressed from alcohol and marijuana to Percocets, Roxicodone, and sniffed and then injected heroin by the time he was an Indian Hills High School junior—had needed to detach from that life, the addict’s life of chaos and damage.

Mark was arrested, held on a half-million dollars in bail with a manslaughter charge pending, and vilified in national media. He ended up putting his head through a noose in his cell but was unable to take the final step.

It was a far cry from the days of his youth, when he was a straight-A student, president of the student council, and captain of the basketball team at prestigious Don Bosco Prep.

“Every addict out there stuck in addiction, the most comforting thought of their day is dying. So remember that the next time you want to judge an addict. We’re dying inside,” he said.

Mark got probation but hadn’t hit rock bottom yet. There is much more to the brothers’ story. Go to an Alumni in Recovery (AinR) event and hear it for yourself.

(And fortunately, the child, saved by paramedics’ administration of Narcan, made a full recovery in the hospital.)

Approximately 120 members of the Pascack Valley community turned out to the Westwood Community Center on March 2 for AinR’s latest event on the disease of addiction and the opioid epidemic, hearing from Craig, Mark, and others—including, from the audience, Craig and Mark’s father.

They were backed by a silent but hardly voiceless chorus: approximately 100 portraits of the dead—area sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers—that comprise the growing “Black Poster Project,” a labor of love created by Haworth’s Dee Gillen after the loss of her son, Scott, to a heroin/fentanyl overdose in 2015 at the age of 27.

The bright and happy photos would be at home in yearbooks, dean’s list announcements, and vacation updates. They could be our sons or daughters. The subjects hadn’t intended to be memorialized in this way.

AinR, a 501(c)3 non-profit organization, is a group of dedicated local people from the recovery community, along with parents who have lost loved ones to addiction.

The evening also brought an update from Police Chief Michael Pontillo on the borough’s participation in the Heroin Addiction Recovery Team (HART) program, in which individuals facing addiction can come to police headquarters to be connected with a specialist who can help them in their recovery.

And it had support from New Bridge Medical Center, Westwood NJ Stigma Free, the Borough of Westwood, and additional resource providers.

Present as well were members of the Borough Council and River Vale Police Lt. John DeVoe.

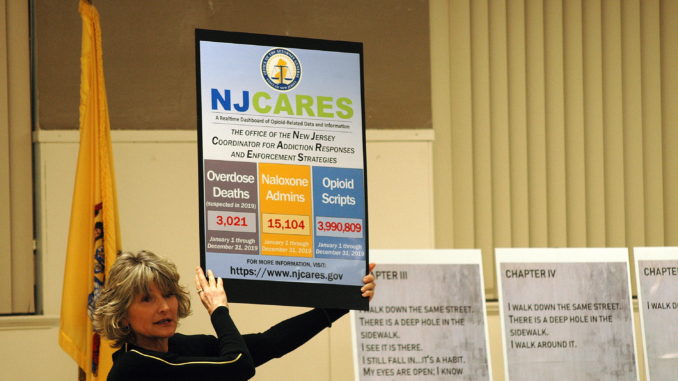

Guest speaker was Sharon M. Joyce, director of NJ CARES, who praised AinR—which delivered some 80 presentations to schools and community centers last year—and said heroin use has increased across the United States among men and women, most age groups, and all income levels.

Joyce said that in 2019, fully 3,021 people in New Jersey died due to drug overdoses, with 143 of them in Bergen County. She said the number could have been far higher, as there were 665 Narcan employed “saves” in Bergen County in the same period.

Craig, 28, sober since June 24, 2013, noting the posterboards, said, “The reason that I’m here today is because this type of thing reminds me who I am and where I can be. I could be on a board tomorrow, right here. This helps me stay sober.”

He later said, “I believe this is a disease I was born with. I believe that one way or another I was going to be a drug addict.”

Mark, 31, sober since April 20, 2015, said, “The stigma is that we’re bad people: that we rob and steal. That we’re the bum on the street in New York City who we’re taught not to go near. But that’s not the truth.”

He explained, “We’re our neighbors, especially in Bergen County, one of the worst areas of the country in terms of addiction. And nobody wants to talk about it.”

He added, “Addicts are not bad people trying to get good; we’re sick people trying to get well. And if we treat it like that I believe more people will get help—the help that they deserve and need.”

Mark said, “My brother and I are the fortunate ones. When we get asked to speak we say yes, we don’t even care where we’re going or what we’re doing, because we know that the only way to solve this problem is to tackle it head on.”

Gillen said her son Scott was a scholar and an athlete, a warm and charming young man, who experimented with opioids, became hooked, and died.

His roommate found him in the bathroom of their Boynton Beach, Florida apartment. His autopsy revealed fentanyl in his system.

Gillen said one of the most striking things about tending to his apartment and closing out his life was how neat, clean, and tidy everything was. His shoes were lined up. His bed was made.

“There was no sign of a relapse in progress. I wouldn’t say we were shocked because we’d been through this before, but it’s just another sign how powerful this beast is,” she said.

She added, “Addiction did its job well with Scott.”

She started the Black Poster Project with a post prior to Overdose Awareness Day 2019. Photos from victims’ families—themselves victims—have been pouring in since.

A unique view

Nancy Labov, founder and director of AinR, has more than 20 years of experience working in the field of addiction nursing and counseling. She said the perspective of each speaker helps attendees understand this powerful brain disease.

“Recovering people are uniquely able to give a complete perspective of the disease process. Parents who have lost their children, primarily to opioid overdoses, courageously speak on what to look for, how to find help, and the reality that drug abuse can be fatal,” she added.

She said the Westwood event “went so well. It’s actually starting to gel, the idea to encourage people to come out and be part in a proactive way to do something about the opioid epidemic.”

She said from her car on March 5, on her way to present a “Not Even Once” assembly at Park Ridge High School, that the conversation is gaining traction.

“We want to see the conversation continue to grow. You never know who needs help on any given day,” she said.