WOODCLIFF LAKE, N.J.—For 57 years, U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Paulie Becker carried Vietnam with him on his back — what he did there, and what came after. It ground him down, angered him, left him in pain both physical and spiritual.

Becker has said that when he finished his special operations service nearly six decades ago, he came home to hostile crowds — the reception was cruel, and scarring: whatever he’d done for his country, the country didn’t want him back.

In one memory Becker has shared, he recalled landing in Oakland, Calif., and being met by protesters who spat, threw garbage, and hurled insults like “baby killers” at him and other returning service members.

This month, Becker went back to Vietnam for the first time since the war — a weeklong trip organized by Scotty McDowell, aimed, he said, at making peace with what he’d carried for nearly six decades. And when he returned, Jan. 9, he didn’t come home quietly.

And he was cheered.

“Who loves ya,” McDowell told him in the car ride from the airport as the home crowd — starting at Demarest Farm in Hillsdale — appeared before them. “This […] country does! And don’t you forget it. And don’t you forget it.”

Becker was stunned. Surprises upon surprises.

The welcome back continued to Woodcliff Lake, perhaps standing in for Oakland, or New York City, or Becker’s new town, Wappingers Falls, N.Y., included residents and police and firefighters lining Wierimus Road in a parade, sirens blaring, lights flashing, Old Glory hoisted high, and news cameras. The loving faces of community.

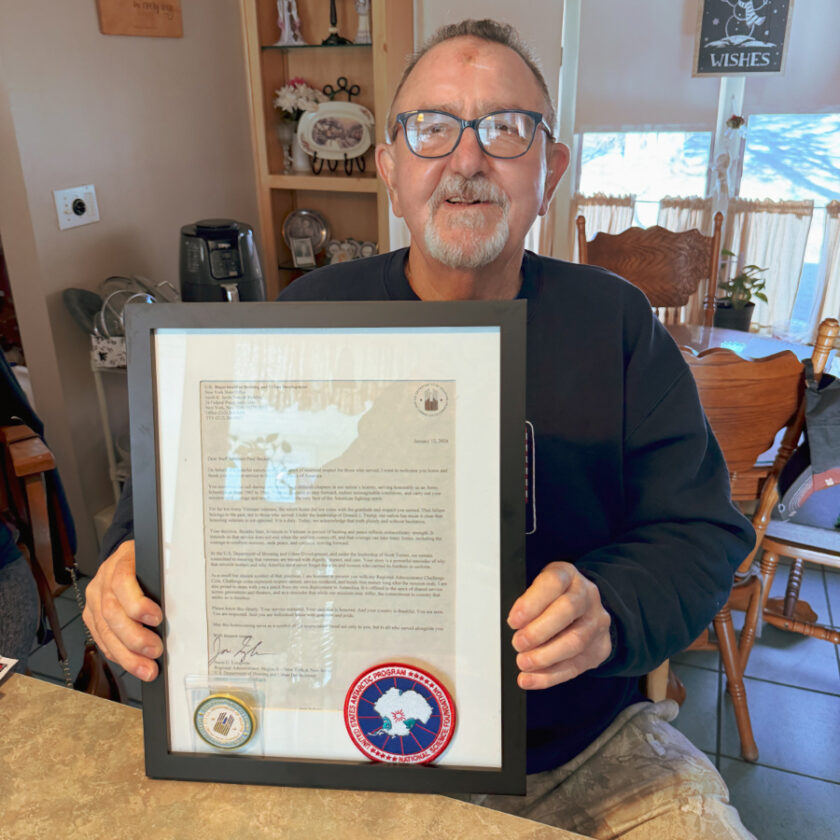

Afterward, Becker fielded messages of support from far beyond Bergen County, including a congratulatory video from retired Navy SEAL and New York Times bestselling author Jason Redman, and a letter and commemorative challenge coin from federal housing official Jason G. Loughran, which bore the names of President Donald J. Trump and HUD Secretary Scott Turner.

For Becker, 78, the most important part was the feeling, at last, of being received.

On Friday, Jan. 9, Becker returned from Vietnam and was greeted along Wierimus Road by residents who came out to welcome him home — a homecoming he told the crowd he had never truly received.

“It was phenomenal, ’cause I had never had that,” Becker said, his voice catching. “Even the homecoming parade in New York City. I didn’t go to it.”

He paused, looked down, and said the thing he has carried quietly for decades.

“I even suffered inside for 57 years… for things I did,” he said.

Becker told the crowd that when he came home from the war, he once went to a priest and asked if God would ever forgive him.

“The priest told me, ‘God has already forgiven you,’” Becker recalled. “‘It’s up to you to forgive yourself.’”

That, Becker said, is what the Vietnam trip was for.

“This trip was basically about… to turn around, and come home, and put the war at rest,” he said. “Get on with my life before it’s too late.”

“It means everything to my heart,” Becker added. “It restores my faith in the American people. But there are people out there that really care. And whether it’s 57 years later, it was totally awesome.”

Becker’s wife, Maureen Launzinger, told reporters the impact of the trip showed up immediately. “I really could see a difference in his whole demeanor,” she said.

The welcome was organized by Woodcliff Lake resident Scott McDowell, who traveled with Becker to Vietnam.

McDowell said he wanted Becker to receive a “proper welcome home” this time around — something that met him with respect instead of scorn — and that he raised the idea with the Woodcliff Lake Police Department, which was immediately on board. As word spread, other first responders and residents joined in, and what began as an escort evolved into a larger community homecoming.

McDowell’s team encouraged residents to line Wierimus Road with flags and signs reminding Becker that, even late, gratitude can still do its thing. A police escort was planned, along with fire trucks from neighboring towns. Organizers said a bagpiper welcome was planned at the end.

But what mattered most wasn’t the planning. It was that people came.

The mood sharpened into a single, unmistakable moment when Becker arrived at McDowell’s home around 12:30 p.m. — with “God Bless the U.S.A.” playing in the driveway and the street still full of people who had decided he would not come home unseen.

Scottie Mac’s way

McDowell has spent years building a community around one simple idea: if America forgot its veterans, he wouldn’t.

Born and raised in Hillsdale and now living in Woodcliff Lake, McDowell is the founder of “Scotty Mac’s Sippy Poo & BBQ for the Veterans,” a thousands-strong Facebook community that mixes food, humor, and a relentless, almost stubborn kind of gratitude. The group’s name comes from a toast McDowell once posted online — raising a mason jar and saying, “Cheers, everybody! Have a little sippy poo!” — and it stuck.

In 2023, McDowell’s annual Fisher House barbecue at Demarest Farms in Hillsdale drew an estimated 500 people and raised more than $75,000 for Fisher House Foundation, which builds comfort homes where military and veteran families can stay free of charge while a loved one is in the hospital. That year, McDowell told Pascack Press his event had become the Fisher House Foundation’s largest donor for two years running.

McDowell raised $112,000 for the foundation in 2024, the same year the Lt. Col. Luke Weathers Jr. VA Medical Center Memphis Fisher House was dedicated to him.

In 2025 — as the nation marked 50 years since the end of the Vietnam War—he raised another $100,000, and was given the organization’s Patriot Award.

“I felt like America forgot about them [the Vietnam veterans],” he said in an interview connected to the annual barbecue. “So I always get emotional.”

The “Sippy Poo” event, now in its seventh year, has drawn crowds approaching 600, and all proceeds go to Fisher House Foundation. McDowell said he once walked through a Fisher House with tears in his eyes, struck by what his community had helped build.

“Just to see what we did,” he said. “Even to be just a small part of it…”

McDowell owns Innovative Landscapes in Woodcliff Lake. He is not a veteran. He has said he “did a stint” in U.S. Navy boot camp in the early 1980s and quickly proved he was “a pain in the ass,” and that was that. His father served in the U.S. Coast Guard.

Of the barbecue: “It’s what I call a Scottie Mac bubble,” McDowell said in 2023. “People can come to the page, cook, have fun; there’s no politics, there’s no animosity, there’s nothing but positive feelings… and our main focus is to make the veterans feel at home and thankful for the service.”

He has shared that passion with his children.

“Together we visit local VFWs and American Legion halls,” he said. “We often go around and shake the hands of our heroes and thank them for their service.”

‘He was a ghost’

McDowell said he met Becker eight years ago at his family’s upstate campsite, where he keeps a camper. The connection started with McDowell’s son, Chase, who was 7 at the time. He noticed a group of men wearing similar hats and asked his father if they were part of a team.

“He’s like, ‘So what’s those guys that wear that same hat? Are they on some sort of a baseball team together?’” McDowell recalled.

McDowell told him they were veterans, and that from then on, when they saw one, they would shake his hand and thank him.

That led them to Becker.

McDowell said Chase thanked Becker, and Becker’s reaction stayed with him.

“He said, ‘You’re raising your kids right,’” McDowell recalled, adding that Becker told him he had never had a young kid come up to him and thank him before.

From day one, McDowell said, Becker felt like family. And over the years, McDowell watched how much Becker carried.

“He was angry all the time,” McDowell said. “Angry at nothing.”

McDowell said Becker served three years in Vietnam, including tunnel work. Even by the standards of warfare, his work was… dirty.

“He was a ghost,” McDowell said.

McDowell said Becker was injured near the end of his service, and that the effects followed him for decades. He said Becker only recently received significant medical care.

“Fifty-six years later he

finally got back surgery, last year,” McDowell said, adding that Becker had been “blown up coming out of his last tour in his tunnel.”

Going back

The decision to return to Vietnam came after Becker reached a place where he could act on change he had previously dared only dream.

“He said, ‘I was talking with my therapist, and she said, maybe it’s time to go back,’” McDowell recalled.

McDowell asked if he could go too.

“I looked at him straight in the face,” he said. “‘Would you mind if I come with you?’”

Becker’s answer, McDowell said: “I would be honored.”

They left New Year’s Day, flying from JFK to Korea and then on to Vietnam.

For McDowell, it was a major jump. He said he hadn’t flown much in his life, and that before this trip his only regular flying had been domestic.

“I used to go to Moab, Utah, mountain biking every year,” McDowell said.

In Vietnam, the trip unfolded simply. They visited a war museum and then spent most of their time taking in the city and talking.

“We really only kind of went to the museum and mingled into the culture around town,” McDowell said.

Both men were sick for much of the trip, he said — McDowell early on, Becker later — which slowed everything down.

“We both were pretty sick most of the trip,” he said. “I was the first half. Paulie was the second half. So a lot of sitting around talking.”

They stayed in a Vietnamese-run hotel called La Siesta, McDowell said, where the staff treated them with remarkable warmth. At times, the rhythm of the trip was simply being outside, watching the street, and letting the days pass.

“We actually used to sit out in front of the hotel and people-watch for three to four hours at a clip,” McDowell said. “And the staff used to bring us out all different kinds of herbal tea to try and help us feel better.”

McDowell said they were advised not to wear military clothing or veteran hats while in Vietnam.

Still, he said, Becker was embraced.

At one point, a hotel staff member told them his grandfather, 98, had served in the war, and was a decorated former officer, McDowell said. The grandfather sent a message to Becker by phone.

“He said to tell Paulie, ‘Welcome to my country,’” McDowell recalled.

A mark that would stay

At some point, the two men decided they wanted something that would not fade into “a trip we took.” They wanted something that would stay.

They got matching tattoos — the Temple of Hanoi, a common symbol in the city — as a way to make sure they would always remember the experience.

“We wanted something that really reminded us of Vietnam,” McDowell said. He said the temple was their first choice out of a couple of possibilities — and once they committed, the symbolism only deepened.

Becker placed his tattoo on his wrist.

McDowell’s tattoo became part of a leg sleeve he said he is finishing. “If it was up to me I would have done more to my leg,” McDowell said with a laugh.

Even the tattoo, though, wasn’t the most unexpectedly personal part of the trip. McDowell said the experience brought them into contact with people who had their own losses — and who seemed to see something meaningful in the meeting.

McDowell shared a photo from the trip of a young Vietnamese woman, Anh, he said gravitated toward the two men.

McDowell said the woman told them she had recently lost her father in a motorcycle accident, and that meeting Becker and McDowell felt, to her, like something timed — not random.

“She said that God sent us for her at this time in her life,” McDowell said.

A message from a different generation of war

After Becker returned home, he received a congratulatory video message from Jason Redman — a retired Navy SEAL, New York Times bestselling author, entrepreneur, and veteran advocate — who had to connect.

“I had some friends tell me that you just went to Vietnam… to make peace with the demons that all of us carry that have been to war,” Redman said. “Number one, welcome home, brother. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate you. You set the example for us younger warriors.”

Redman thanked Becker for his service and encouraged him to keep going forward.

“Welcome home, man,” he said. “Continue to live greatly.”

‘Your service mattered… You are seen’

Three days after the homecoming, Becker received a letter dated Jan. 12 from Jason G. Loughran, regional administrator for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Region II office (New York and New Jersey).

The letter, addressed to “Staff Sergeant Paul Becker,” thanked him for his service and acknowledged the history many Vietnam veterans lived through.

“For far too many Vietnam veterans, the return home did not come with the gratitude and respect you earned,” Loughran wrote.

Loughran praised Becker’s decision to return to Vietnam “in pursuit of healing and peace,” and wrote that courage can mean facing memory and continuing forward.

“Please know this clearly: Your service mattered,” Loughran wrote. “Your sacrifice is honored. And your country is thankful. You are seen.”

The letter was accompanied by a HUD challenge coin bearing the names of President Donald J. Trump and HUD Secretary Scott Turner, and a United States Antarctic Program patch that Loughran wrote came from his own deployment to the bottom of the world.