PARK RIDGE—If you think small-town politics is bad today, you should have seen Park Ridge of the late 19th century.

The coming of the railroad in 1870 had brought a new suburban population to Park Ridge, and old ways had been at odds with the modern world ever since. On one side you had the traditionalists, those bastions of early Pascack whose families had tilled the same land for generations. On the other side were the newcomers, many of whom commuted into New York City for work.

While the farmers held tight to the ways of their forefathers, the new residents valued modern amenities and education, even if that meant higher taxes. Each side looked down on the other and insults flew back and forth. Those were wild election years in Park Ridge, as local candidates were divided along those lines and both sides played dirty.

By the late 1880s, one matter that both sides could agree on was that Park Ridge, with an influx of new residents, had outgrown its little two-room schoolhouse. The problem was, it was proving impossible to reach a consensus on how to remedy that.

The commuters had big ideas: they wanted a brand new eight-room schoolhouse, allowing a separate room for each grade. For the farmers, this was pure nonsense and would be an unforgivable waste of tax dollars.

When the time came to vote on the new schoolhouse, the farmers tried something rather underhanded. (In fact, today we would call it voter suppression.)

They found an old law on the books that said voting could take place at any time of day the Board of Education saw fit, instead of in the evening, as was customary. With a majority leaning toward the farmers, the Board of Education decided to hold the vote in the afternoon—knowing full well the commuters would be out of town, at work in New York City, and hardly anyone would give up a day’s pay or risk their job by staying home.

In retaliation, on the afternoon of the vote the commuters sent a series of speakers whose job it was to filibuster, conducting a sort of marathon of speeches and debate, stretching things out until the city men could get home that evening.

A few daring commuter wives even turned out to cast votes in place of their husbands. At first they were turned away on the grounds that women were not allowed to vote.

However, the wives noted that while the law prohibited their voting on candidates in elections, women did have a right to vote on funding issues. Of course, no sooner did this come to light than the farmers’ wives rallied to cancel them out by casting their own votes. The commuters’ ambitious school proposal was ultimately voted down.

Eventually both sides were able to reach a compromise. A sum of $10,000 (equivalent to about $320,000 today) was approved to build an addition to the existing school. The school was located in the area of the sports fields behind the present-day Park Ridge High School.

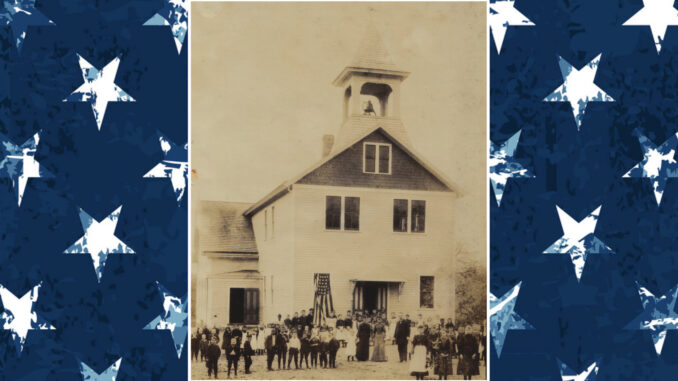

Park Ridge’s new schoolhouse, pictured above, was finished in 1890. The two-story wooden building had enough space to hold all students through grade eight. Although the school was larger than its predecessor, it still lacked basic amenities we take for granted. There was no indoor plumbing; the children used an outhouse behind the building.

The 1890 school was used for fewer than 20 years before it became too small for the ever-expanding population. In 1908 a new and much larger school was built at the corner of Park Avenue and Pascack Road. When that school was destroyed by a fire in 1920, the present high school was built to replace it.

— Kristin Beuscher, a former editor of Pascack Press, is president of Pascack Historical Society in Park Ridge and edits its quarterly members’ newsletter, Relics.