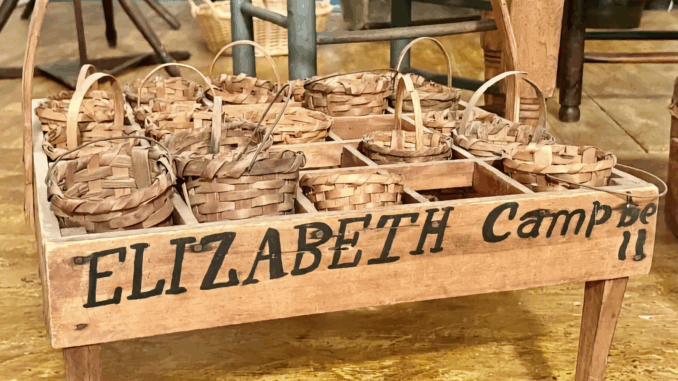

PARK RIDGE, N.J.—These charming strawberry baskets were owned by Elizabeth Campbell (1850-1931) during her childhood in Park Ridge. Years ago, Bergen County was famous for its strawberry harvests that were shipped by train, wagon, and boat for sale in New York and other cities. Note that an enthusiastic young Elizabeth had painted her first name prominently on the basket holder (called a hamper), only to realize she did not leave adequate space for her last name. It’s a miscalculation we all made as children.

For the farming families of the old Pascack Valley, June signaled one thing above all: the strawberry harvest.

During the winter months, when people were indoors and there was less farm work to be done, families had been busy handcrafting the small, hand-woven hickory baskets—called punnets—that would be essential come summer. By June, it was time to put them to good use.

Strawberries grew in the Pascack Valley in vast quantities and were coveted in the produce markets of cities like New York, Paterson, and Newark. It was the first fruit of the season, and this meant a quick return and ready money for the farmer. It gave him and his family employment, the boys and the girls earning money as berry pickers, and even the wife and older generation finding work in the berry fields.

The noted New Jersey historian John T. Cunningham wrote in 1963, “Wild strawberries brightened the hills of New Jersey when the first colonists arrived. Revolutionary War soldiers breaking out of winter camps at Morristown feasted hungrily on the toothsome fruit, and children walking the fields knew the joys of the June berry. Nevertheless, it took market-minded Bergen County farmers of the early 19th century to make the free-growing berry a delicacy to tempt the leanest of pocketbooks.”

It was those wild berries that Bergen farmers first brought to the city market.

Cunningham wrote, “They sold their fruit from homemade splint baskets hung on poles across their shoulders. As they walked the streets of downtown New York, the strawberry vendors sang, Berries! Berries! Bergen berries!”

Housewives eagerly bought up the berries as fast as Jersey could produce them.

“Bergen farmers, long attuned to the desires of the New York market, took it from there. They selected the best of the wild plants, cross-bred and fertilized them, and by 1840 had developed bigger and redder varieties, including the Hauboy and the noted Scotch Runner. Thereafter, for more than 50 years, the upper parts of Bergen and Passaic counties went strawberry wild every June,” explained Cunningham.

In the 1930s, Pascack Historical Society founder John C. Storms recorded in detail the strawberry seasons of his boyhood. He was born in Park Ridge in 1869, a time when the area was entirely rural.

“Schools were suspended around June 1 to let the farm boys and girls pick berries, and the vacation lasted for six weeks,” Storms wrote. “The entire family participated in the picking—men, women, little children. Work began early and continued until late, with only the briefest possible time for a hasty noon lunch.”

Each person carried a supply of empty baskets held on a string that passed through the handles. Filled baskets were placed in the grass behind the pickers as they went along, to be gathered up at the end. The family would finally head inside for dinner when it was too dark to see the berries. In June, that was well into the evening.

“Each little basket was covered with a large chestnut or hickory leaf drawn under the handle and tied with a piece of bark passing under the bottom of the container. This kept the berries fresh and prevented their spilling,” Storms wrote.

Every week a special “strawberry boat” took the loads of berries from Bergen County down the Hudson River, landing them on the dock at the foot of Christopher Street in Manhattan. Later, when the Northern Railroad through Closter opened in 1859, the farmers would take their berries by wagon to be loaded onto the special “strawberry train” that ran nightly.

While full baskets were handled with care, the return trip was a different story. Empty containers—meant to be reused—were jostled and often damaged, necessitating a new round of winter basket-making the following year.

DID YOU KNOW | The Lenape, the indigenous people who were the first to set foot in the Pascack Valley, had a word for the wild strawberries they found here: w’tehim. The Jersey Dutch, the first permanent settlers in the 18th century, adopted the Lenape word into their language as tahaaim.