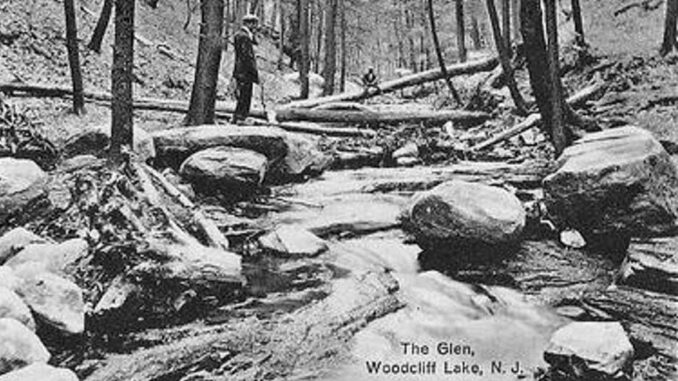

WOODCLIFF LAKE—We imagine it was right around this time of year that the above photograph was captured in the Glen in Woodcliff Lake in the early 1900s.

The Glen has been a part of the culture of the Pascack Valley for generations. A deep ravine cut through the sandstone by the Bear Brook, the spot is a rare natural gem in the middle of our suburban landscape. Even in the early 1900s, when the area was still very rural, the beauty of the Glen made it a favorite spot for walks and picnics. It exists today, largely unchanged, thanks to successive owners who refused to let the modern world mar a natural wonder—first James Leach, and later Daniel H. Atkins of Montvale, who bought the property in 1921.

The region’s early Dutch settlers were well aware of the site, but they viewed it in a much less sentimental light.

Local historian John C. Storms, founder of the Pascack Historical Society, wrote in 1956, “The Dutch called it ‘Spook Bergh’ (the last word is pronounced Baar). This meant Ghost Hill and was believed by the ignorant and superstitious to be a resort of demons. It is a cleft or gorge in the land which is level around it, tree-grown and shaded even in otherwise bright sunshine. The sound of rippling water coming up from the depth of a 100-foot abyss gave color to the fantastic tales which were commonly accepted.”

By the start of the 19th century, ghostly tales of the Glen were seen as the silly fantasies of an older generation. Instead, the land became a popular recreation site. Fishermen would come long distances to try their luck at catching the large trout that were plentiful in the stream. Other visitors found an excellent site for camping at the lower end of the park, and many day-trippers used the spot for picnics.

Historian Storms, who grew up in Park Ridge in the 1870s, recalled the names the local kids gave to various points along the course of the brook. There was Cold Spring, a section bubbling out of a red sandstone basin at the side of the stream. Shelter Rock was an overhanging sandstone shelf under which the children stopped for cover on rainy days on their way home from school, or when fishing. The spot they called Dead Man’s Hole was much less menacing than its nickname suggested. This was a popular swimming spot, chosen in part because two large boulders made a private spot for getting undressed.

“The old timbers of John Lutkins’ sawmill came in for much exploration, but the constant magnet that drew the boys’ attention was a large exposed outcropping of sandstone in the bushes a short distance from the beaten path,” Storms recalled. “It was level with the ground and someone had drilled a hole in it, perhaps hoping to break it up into building blocks. There was a story among the lads that an Indian had been buried underneath the stone. It was said and confidently believed that if an iron bar was pressed down into the hole, by some magic the entire stone would raise up as on a hinge, and the skeleton of the dead man would be exposed to view. Many attempts were made to make the discovery.”

The Glen exists today thanks to successive owners who refused to let the modern world mar a natural wonder. At the turn of the 20th century, owner James Leach allowed the public to make use of the spot. Local church groups held outings there, picnicking and swimming in the brook. A 1902 news clipping mentions that Seventh-Day Adventists were using the spot for baptisms.

As time went on, and word spread about Leach’s Glen, increasingly large parties of picnickers, including busloads of people from outside town, began visiting regularly and causing damage. The Erie Railroad wanted to capitalize on the popularity and approached Leach with a proposition to buy the property and create a resort, including an amusement park and concessions.

“The proposed plan was to build a single-track spur line from a site near the present Woodcliff Lake station to the park. Although the company tried long and strenuously to secure the property, Mr. Leach refused to sell it, knowing that the Sunday excursion business would be a detriment to the park and a nuisance in the community,” Storms wrote.

Leach refused the railroad’s money in favor of protecting the land. He closed the park to the public, except for approved groups and visitors.

After Mr. Leach’s death, Daniel H. Atkins of Montvale bought the property in 1921 and the public was once again admitted—that is, until Mr. Atkins was forced to send workers on Mondays to clean up all the trash left behind by the weekend crowd. The public was barred once again.

In the 1950s the Atkins estate gifted the land to the Borough of Park Ridge for use as a public park.