As Park Ridge prepares for Thanksgiving, it seems fitting to revisit the life of a man whose nickname still echoes faintly through local history: “Turkey John” Blauvelt, more properly John A. Blauvelt — farmer, storekeeper, Park Ridge’s first postmaster, real estate speculator, and one of the quiet architects of the jumping upper Pascack Valley.

Largely forgotten today, 150 years ago everyone knew him. In the sparsely settled Pascack region, social circles were small, and Blauvelt’s constant involvement in village life ensured his name was familiar to nearly every household.

Blauvelt was born 200 years ago in Rockland County, the son of Abraham Blauvelt, a farmer, and his wife Hannah (or Annaetje, in Jersey Dutch) of Nanuet. His grandfather, Lt. Cornelius J. Blauvelt, served with the New York Militia during the Revolutionary War, anchoring the family firmly in the early story of the region.

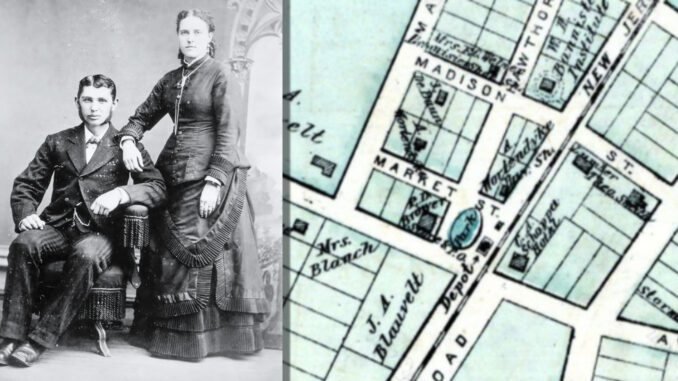

In 1846, at 21, John married Ellen Perry, then 18, at the Saddle River Reformed Church. They had one daughter, Hannah Priscilla, named for their two mothers. Blauvelt operated a general store in Old Tappan near what is now the River Vale border, and at some point acquired the nickname “Turkey John,” for reasons lost entirely to history — a rarity in a region where people’s quirks were well remembered.

The family arrived in Park Ridge in the early 1860s and settled on the northeast corner of Park and Maple avenues. The house stood for many decades before its eventual demolition, but in its time it was a known local landmark.

Blauvelt’s ambitions, however, extended beyond shopkeeping. He ventured into land development, a move that would permanently alter the course of Park Ridge and its neighboring towns.

Working with David M. Demarest, president of the Irving Savings Bank of New York City, Blauvelt subdivided the former Isaac D. Perry estate — nearly 100 acres in eastern Park Ridge. Together they carved this farmland into hundreds of residential lots and mapped an entirely new suburban-style neighborhood in what was then a rural village.

Their advertisements targeted New York City residents, urging them to seek a healthier life in the countryside and take advantage of the newly installed railroad service for commuting. These early newcomers — the Pascack Valley’s first wave of suburban commuters — marked the beginning of a lifestyle shift that shapes the region to this day.

But Blauvelt’s influence went even further. The path of the Pascack Valley rail line north of Hillsdale has a distinctive bend northeastward. Originally, the plan was quite different: the Hackensack & New York Extension Railroad intended to drive the tracks northwest, crossing Pascack Brook and continuing in a straight line toward Spring Valley.

Under that alignment, rail service — and therefore business districts — would have centered along:

- Woodcliff Avenue and Pascack Road in Woodcliff Lake

- Fremont, Ridge, and Colony avenues in Park Ridge

- The west side of Montvale, paralleling Spring Valley Road

- Those quiet residential streets would today be busy downtown corridors.

Why didn’t it happen? The farmers along that western route refused. They objected to their land being split in two; sparks from steam engines possibly igniting fields; locomotives spooking horses; cows becoming anxious and failing to give milk

With the route stalled, Blauvelt and Demarest stepped in. They offered the railroad free right-of-way across their own property, proposing a path east of Pascack Brook instead. The railroad accepted. It was a mutually beneficial deal: they supplied the land, and the railroad brought value to their new residential development.

Thus, the present course of the Pascack Valley Line took shape, opening in 1871. Train depots in Woodcliff, Park Ridge, and Montvale became anchors of early village life, with general stores, hotels, and eventually apartment houses springing up beside them.

Without Blauvelt’s intervention, the map of the Pascack Valley — and the daily rhythms of thousands of commuters — would look entirely different.

Despite his lasting impact, Blauvelt did not live long enough to see Park Ridge blossom. His wife Ellen died in 1878. He remarried the next year, but died weeks afterward, at 54.

He rests at Pascack Cemetery, buried alongside Ellen; their daughter Hannah; and Hannah’s husband, Alonzo Campbell, a Park Ridge farmer and undertaker from the well-known Campbell wampum-making family (learn more at the Pascack Historical Society museum).

Had Blauvelt lived into the new century, he would have witnessed a village transformed — thanks in no small part to choices he made decades earlier.