It’s an incident that until now had been lost to history. But for the people who witnessed the horrifying scene on April 29, 1929 in downtown Closter, it must have been seared into their memories.

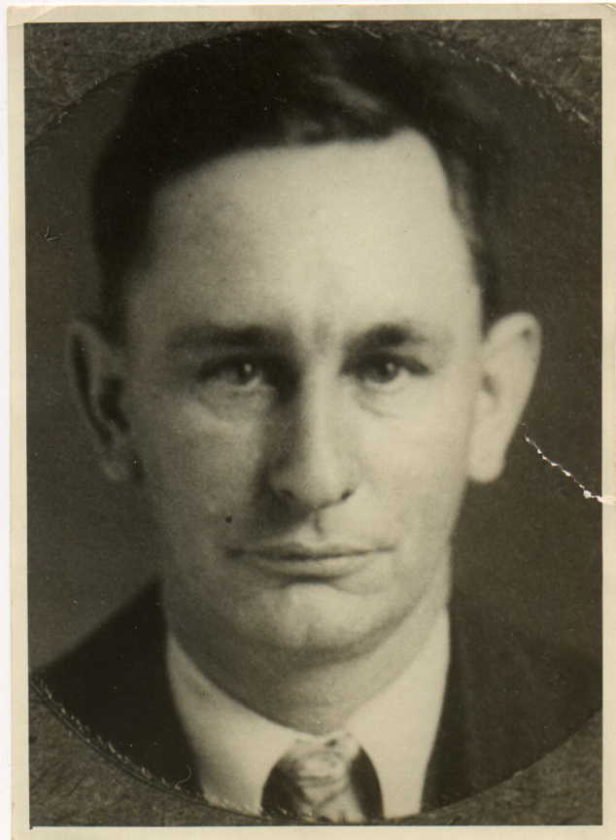

Thirty-nine-year-old bus driver Herman Hundemann Jr., whose parents lived on Hardenburgh Avenue in Demarest, was behind the wheel of a Public Service Interstate bus traveling through Closter just before midnight that night.

As witnesses described, the bus came down Main Street (Closter Dock Road) in the direction of the tracks, halted for a moment about 15 feet from the crossing, and then kept going.

At the same time, a Northern Railroad train was coasting into Closter from the direction of Northvale, traveling about 35 mph. The engineer had already begun to apply the train’s brakes, he told police at the time, when a bus suddenly loomed under his headlights.

The train struck the bus just ahead of its center. The vehicle was sent upwards and away, then crashed back down to the ground, at which time the train ripped off the left side of the bus and hurled it some 65 feet away into the side of a barn. The train ground to a halt about 600 feet ahead.

The bus was left a tangled wreck, with shrapnel dotting the rails from Main to High Street. The train crew jumped down and ran back to the bus, where a police patrolman was already trying to extricate the injured and panic-stricken passengers. Hundemann was killed in the crash and seven other people were injured, three of whom were unconscious.

The crossing gates were raised at the time, the watchman having gone off duty at 11 p.m. (In those days, the gates were raised and lowered manually as trains arrived and departed.) During off-hours the crossing was protected by a bell, a horn, and a warning signal. Yet, crashes were not unknown there. Less than a year earlier, a heavy truck was struck by a westbound train and hurled against a watchman’s shed, demolishing it. It was a big commotion, but nobody was seriously injured.

The only person who knew for sure why the bus drove into the path of a train had perished in the crash, but police believed that Hundemann had somehow failed to see the locomotive’s headlight and that the noise of his own engine drowned out the noise of the train.

As a matter of procedure, the train engineer and conductor were arrested on a charge of manslaughter. Bergen County Prosecutor A.C. Hart ordered their release, stating that “in the interests of the public’s convenience, these men cannot be locked up tonight.” The train continued an hour behind schedule.

One of the injured passengers, William Krause of New York City, died three days after the accident.

After the crash, the Northern Railroad expanded the hours that gatemen were on duty at the Main Street crossing. Starting in September of 1929, gatemen were present day and night, except for the hours from 1:45–5 a.m.