PASCACK VALLEY—In summer 1930, transporting an ear of corn into New Jersey was a serious offense. Caught smuggling the crop? You faced a fine of $500—a nearly $10,000 chunk of change in today’s money.

Why the commotion around corn that summer?

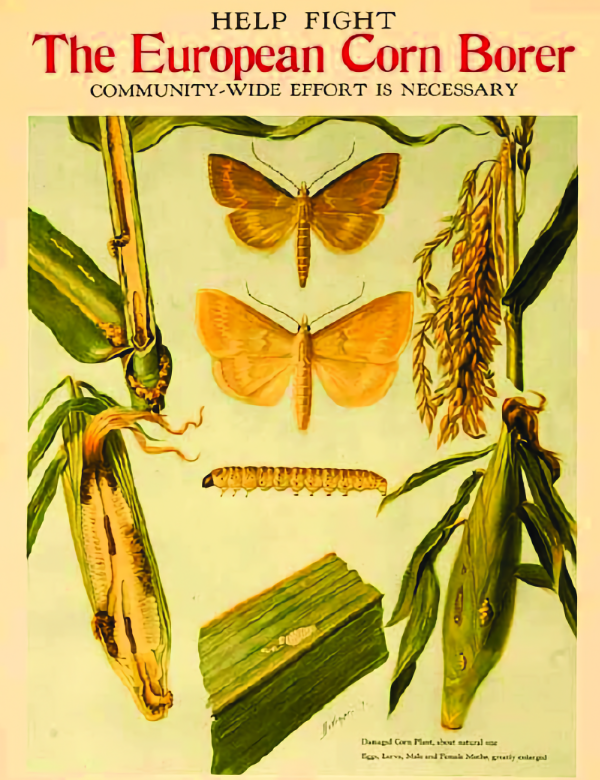

A pest, the European corn borer, was doing some serious damage in surrounding states after making its way across the Atlantic.

The insect had come from Hungary or Italy in shipments of broom corn (a type of sorghum used to make brooms) and was discovered in Massachusetts in 1917. By the late 1920s it was in New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, where the moth—or more specifically, its larvae—was burrowing into stalks and ears of corn and ruining fields.

Bergen County in 1930 had approximately 19,000 acres of farmland. Of that, nearly 3,000 acres were fields of sweet corn. The federal government put in place a quarantine to ensure the infestation wouldn’t take hold here. That summer, not a single ear of corn was to cross state lines into New Jersey.

“The invasion of the European corn borer has menaced one of the nation’s important crops. The only way the invasion can be checked is to shut off the transportation of corn from one area to another so that the battle against the borer in the corn fields is not defeated by new invasions of the pest via automobile,” the Jersey Journal wrote on Aug. 9, 1930.

Checkpoints operated on interstate roadways 24 hours a day, and everyone was required by law to stop at them. A uniformed man from the Department of Agriculture would come to your window and ask if there was any corn in your car. (Yes, this really happened, and it caused major traffic backups that summer.) If your answer caused any suspicion, the inspector was empowered by the federal government to search your car and seize any corn he found.

Of course, it was impossible for the inspectors to search every car. In almost all cases, if you said you were not carrying any corn, you were waved right through. The effort relied heavily on the public’s honesty—and people generally tolerated the inconvenience, understanding that it was for the greater good.

The Jersey Journal reported, “The trouble of opening the rumble seat of an automobile is little. The job that the corn borer inspector is on is a big one. To object in helping in the big job by doing a little one is petty.”

Of course, there were always those who wanted to flout the law simply for the sake of it. Some would hurl profanity at the inspectors, while others just blew through the checkpoints. There were also the amateur smugglers, who seemed to get a thrill out of risking a $500 fine for 40 cents’ worth of out-of-state corn.

“This may seem farcical to some,” the newspaper continued, “but it is a fact that sane, sensible, moral women, who would not think for one minute of breaking any other law, have been found carrying corn underneath their skirts to escape the inspectors. Corn has been camouflaged in all kinds of packages and bundles to get it across, just the idea of outwitting the inspectors being reason enough for such proceedings.”

As with all jobs that have a graveyard shift, the inspectors working at night encountered some especially interesting individuals.

“Those on the night shift are continually interrupting petting parties and more than one female occupant of a stopped car has shielded her face to prevent recognition,” the Bergen Record wrote on Aug. 6, 1930. “Another bane of the night shift’s existence is the wild party returning home inebriated. Once they get stopped it becomes hard to get them started again. They either want to stay there and make whoopee under government protection or insist on telling the inspector the story of their lives.”

Some Rockland County farmers went out of their way by miles to avoid the main roads in bringing their contraband corn to New Jersey markets. Their trucks would snake through the back roads of the rural Pascack Valley to avoid the checkpoints at the Montvale-Pearl River line. Montvale in 1930 had only 1,200 residents, compared with today’s nearly 10,000, and much of the borough was farmland. There were many such routes.

The checkpoints also aggravated the bootleggers. Those were the Prohibition years, when the manufacture, transport, and sale of liquor was forbidden. New Jersey’s rum runners, posing as truck farmers going to market, were known to disguise their illicit cargo inside crates of vegetables or under piles of corn. That trick did not work so well in the summer of 1930.

The quarantine measures were apparently successful in stemming the spread. While the corn borer did eventually make it to northern New Jersey during the 1930s, and farmers did see some losses, the effects were not catastrophic. In the end, Bergen County’s corn production was toppled not by a tiny pest, but by the loss of agricultural land to suburban development.