[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

BY JOHN SNYDER

OF PASCACK PRESS

MONTVALE, N.J.—After Allendale’s Madison Holleran took her own life, loved ones were left asking what clues they might have missed.

The woman who would later write the book on Holleran said she found hints in the same social media tricks a generation of kids use to “perform” an idealized version of themselves.

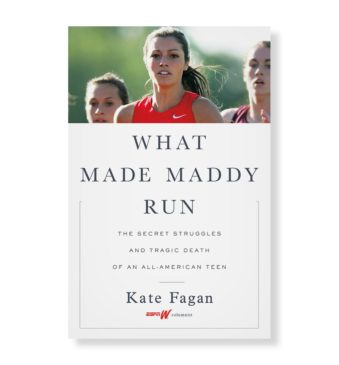

What emerged in ESPN columnist and reporter Kate Fagan’s bestselling book, “What Made Maddy Run: The Secret Struggles and Tragic Death of an All-American Teen” (2017), are anxiety and tendrils of depression familiar to many students.

Holleran, whose father’s side of the family happens to have a history of depression, presented online what Fagan called “the perfect, idealistic representation of a college experience.”

“Maddy herself was under no illusion that she was having the ideal college experience,” Fagan said.

Fagan was keynote speaker at Hills Valley Community Coalition’s parent/teen education program “Split Image: Secret Struggles of Teens” at Pascack Hills High School on May 3.

The program, coinciding with Mental Health Month in New Jersey, also featured a stigma-free Mental Health Resource Fair powered by 50 local, county, and state organizations and practitioners, a book signing by Fagan, and group discussions facilitated by mental health professionals. Just over 500 attended, organizers estimated.

Organizers were Gale Mangold, PHHS student assistance counselor, and Pam Martorana, child and family therapist and owner of Kinderkamack Counseling in Montvale.

Fagan’s message resonated in the packed auditorium, speaking to split image, social media, performance perfection, and the toll it takes on youth.

The coalition is an alliance of community members working to promote a stigma-free and substance-free environment for the families of Hillsdale, Montvale, River Vale, and Woodcliff Lake.

The organization is composed of school officials, municipal leaders, law enforcement officers, business leaders, health providers, faith-based leaders, and residents.

Wendy Sefcik, of “Remembering T.J.” [rememberingtj.org] and the American Foundation For Suicide Prevention presented a survivor’s talk on “What Parents Need to Know” about suicide.

Leading a Q&A were doctors from the New Jersey Psychological Association and Northeast Counties Association of Psychologists.

There also was a contingent of police officers from Hillsdale, Montvale, River Vale, and Woodcliff Lake, fielding questions and encouraging the safe disposal of unused medications.

By the numbers

Every year, more than 40,000 Americans die by suicide. Among young adults, ages 10 to 34, suicide is the second-leading cause of death—behind accidents and ahead of homicide—with more than 4,500 young people taking their lives each year.

The suicide rate among NCAA athletes is lower than the general population—0.93 per 100,000, versus 10.9, Fagan reports.

Between 2004 and 2012, 35 student athletes took their own lives, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maddy’s story

The story of Madison Holleran feels personal to Fagan, who resonated with familiar and familial moments in her subject’s life. One suspects they could have been good friends.

Holleran was a high achiever, leading her Northern Highlands soccer team to two state championships, scoring 30 goals in one season, and winning the New Jersey state title in the 800-meter run in her senior year.

She was heavily recruited for soccer, but when the University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy League school, liked her for track, she took the offer.

“It felt like, ‘How could I not go to the Ivy League if the Ivy League exists?’ Fagan interpreted Halloran as wondering.

As the transition to college wore on, Holleran entered a crisis, deeply and privately held. She appeared to struggle with her choice. She lost weight and became despondent. Her parents noticed irritability.

Yes, she allowed, she wasn’t sure she was on the right path. She wasn’t 100 percent on board with track.

Holleran talked about suicide a week before she returned to school. She did not follow through on a plan to see a therapist.

On Jan. 17, 2014, she bought gifts for her family, took a lovely, artfully filtered photo of her surroundings and posted it to Instagram, climbed to the ninth floor of a Philadelphia parking garage, left the gifts in plain view, and launched herself over the rail.

She’d left a brief note. “I love you all … I’m sorry,” it concluded. “I love you.”

Fagan picked up the story with a striking essay May 7, 2015 for espnW, “Split Image,” which surprised her with hundreds of emails from kids saying they can relate and wanting to know more.

She said some clues in Holleran’s loss suggested themselves after she dived deeply into the 19-year-old’s computer and studied her social media.

Messages that would resound as cries for help in person were offset by cute emojis: a crying smiley face here, a monkey covering its eyes there.

“Nobody can do a monkey covering eyes [emoji] in person. You have a separate set of questions for monkey covering eyes in person. But you certainly have follow up questions,” Fagan said.

“Social media is not an accurate reflection of real life. I don’t think I’m breaking new ground by saying that. I don’t necessarily think that applying that logic is easy,” Fagan said.

She explained: “The version of myself that I put out there isn’t real and I know this isn’t the real version of someone else and yet I’m an hour into scrolling through their Instagram and wishing I were them.”

More questions than answers in depression, suicide

Fagan cautioned, “Nothing I’m going to offer tonight in your mind is going to say, ‘Now I understand this story.’ Because you’re not.”

“When I started reporting it, I was like, I’m going to be the person that’s going to find the ‘Why’ and I’m going to understand this story when I’m done with it,” she explained.

But, she said, “Maddy’s friends told me from the beginning, ‘Don’t do that. Don’t search for that. We want you to share as many of the pieces of this story as you can, but don’t think you’re going to find this one answer.’”

She emphasized that asking about a loved one’s mental health will by no means plant a seed for suicide.

“You are not going to introduce the idea to anyone. You can never care too much. No one’s ever said, ‘I’m really mad because you care too much,’” Fagan said.

Her bestseller on Holleran—Fagan’s second book, following “The Reappearing Act: Coming Out as Gay on a College Basketball Team Led by Born-Again Christians” (2014)—asks us to peel back the layers underneath that logic and consider how social media and technology “might be affecting the brains of our young people and all of us.”

The book also examines cultural trends in anxiety as well as the peculiar culture of success that perfectionists are prone to.

Perfectly imperfect

In the bigger picture, Holleran said, quoting a line suggested by one of her readers, “Mental health is not the absence of mental illness.”

Fagan also drew from a 1996 sermon, “The Fine Art of Being Imperfect,” from Irish pastor Maurice Boyd, and said, “Notice how close perfection is to despair.”

“We want to make sure that any of us who are struggling in a way that maybe mirrors something like Maddy was going through … it’s a really deep struggle. We want to speak to those people. We want to understand how to help,” she said.

She asked, “What do we do and how can we look at our kids where we’re deciding what ways we’re engaging in the world that actually makes our brains feel better?”

In the Q&A with psychologists that followed, Fagan ran the microphone throughout the audience, at one point demurring, “If anyone has any questions about the Sixers, I’ll take those.”

Parents and children in the audience showed they were concerned with the intrusion of apps in the student experience that let subscribers see grades as soon as they’re posted.

One mother admitted to texting her daughter in her classroom as soon as a relatively low grade popped up on her phone.

“That’s too much stress,” she said. “What are we doing to our kids?”

— Event photos by John Snyder.