OF NORTHERN VALLEY PRESS

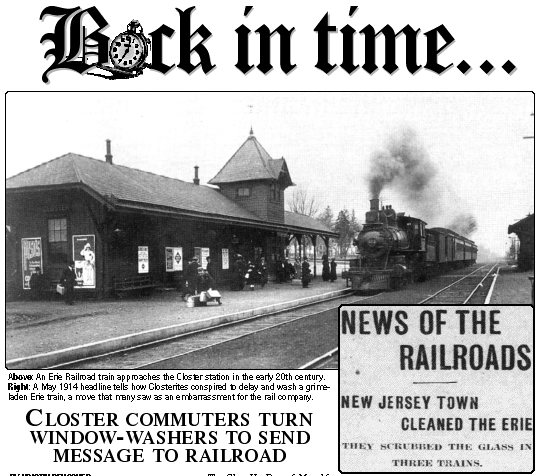

Closter, New Jersey—When the Erie Railroad tried to cut costs by reducing its cleaning staff in 1914, the people of Closter weren’t going to stand for it. They conspired to delay and scrub down the trains themselves, a move that was covered nationwide in newspapers and which some saw as a humiliation for the men behind the Erie Railroad Company.

As the New York Herald put it afterwards, “If the Erie Railroad has any pride in its corporate makeup it must have been injured yesterday afternoon at Closter.”

In April of 1914, the Erie Railroad cut the staff assigned to clean its passenger cars. The windows quickly became dusty and grimy. Newspapers along the line decried the new policy, and local boards of health complained to the company. Finally, Closter residents, armed with hoses, cloths and buckets, took matters into their own hands—literally—to give the trains a thorough scrubbing.

“The Clean-Up Day of May 16, 1914 will take the same place in the history of Closter that the Boston Tea Party of Dec. 16, 1773 has taken in the history of the Massachusetts capital,” reported The New York Times.

While that didn’t exactly happen, for the people of Closter a century ago this was nonetheless a momentous occasion that brought people together for a common cause.

Closter residents hatched a plan: A group of women and children, bogged down with strollers, bags and packages, was to board the 3:20 p.m. train bound for Demarest, and then return to Closter on the 3:30. They were to take as long as possible to detrain at the Closter station, where a crowd of men would be waiting with cleaning supplies.

“At 3:20 the train pulled into Closter, where it was hailed with shouts by about 500 men, women and children,” The Times described. “Before the train came to a stop about 40 wet mops were soused against the windows, and they were handled vigorously.”

Other passengers on the train, unaware of the crusade at Closter, were startled by mops slapping against the windows. Some whose windows were open got quite the surprise.

“Conductor John McMahon and the members of the train crew ran to the platforms, but attempted no resistance when they saw they had a whole community to deal with,” The Times wrote.

Mayor Warren Ferdon told the newspaper, “The train windows were so dirty that the passengers for the last week have been riding through a tunnel for all the light that might penetrate to the cars. If it was any crime to clean them, we will answer for it.”

While the windows were being washed, “the Closter women climbed down the car steps one at a time, and they used every device known to women to make slow progress,” The Times wrote. “The efforts of the trainmen to accelerate them had no effect. The train, which usually stops for two minutes at Closter, was seven minutes in getting away.”

Repeating the process for the 3:30 and 3:45 trains, that afternoon Closter residents scrubbed down three Erie trains. Mayor Ferdon told The New York Times it was the proudest night anyone in Closter could remember.

[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]