NORWOOD, N.J.—Have a school security plan, follow the plan, and believe it’s happening.

In short, that’s what a top county law enforcement official told nearly 50 teachers and administrators at Norwood Public School June 3 to help dramatically boost school security and improve everyone’s chances for survival in the event of a school shooting.

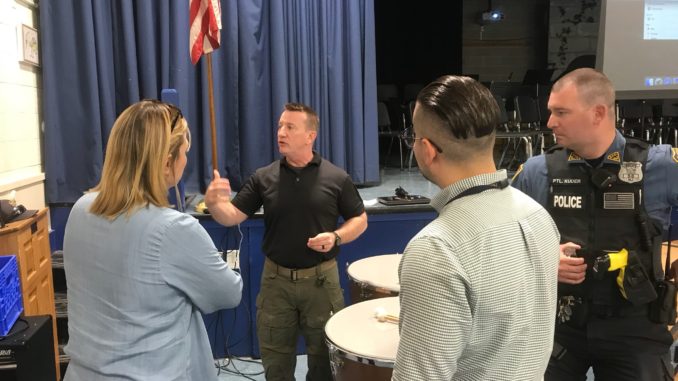

Martin Delaney, Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office senior assistant prosecutor, offered informal training in active-shooter response along with tough counsel and shrewd advice—much derived from a massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida and other well-known mass shootings in schools and public places.

Delaney provided an hour-plus presentation of hard-learned lessons learned, with added parts encouragement and street-smarts, to aid the school’s K–8 teachers in better protecting students.

Delaney provided overall advice and specific tactics—an interactive briefing he has given at any school who has requested his security expertise as part of Bergen County Prosecutor’s Office three training courses provided free to help prepare all school officials, teachers and employees to improve school security.

BCPO spokeswoman Maureen Parenta said 3,400 school personnel took the courses in the past six months, although she was unable to provide numbers of schools that took specific courses.

Local officers visit the Norwood Public School each day for security patrol and walk-throughs, and Norwood Police Officer John Kuder joined the staff and Principal Vito DeLaura at the active shooter security briefing.

Developing a security plan focused on denying unauthorized access and quickly being able to put the school on lockdown is the top priority, Delaney said.

He added that most mass shootings take place in six minutes or less and that teachers and employees “need to believe it’s happening.”

He said people have a “normalcy bias” that prevents them from quickly grasping the reality of crisis situations—especially shootings.

He noted most killers are opportunistic and indiscriminate and look for shooting situations that are “target rich.” They generally don’t open closed doors and enter rooms, preferring easier targets.

He said the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School gunman did not get into any of the locked classrooms but rather fired at victims in plain sight.

According to Delaney, the worst mistake someone can make in a shooting is to disbelieve that they hear gunshots when indeed someone is shooting a gun in a confined area and time to respond is short.

“Panic is the worst choice,” Delaney said, explaining that having an emergency plan in place can save lives.

He said local officers and a regional SWAT team should be at the school within minutes of a shooting. He said an important rule to follow is “make yourself hard to kill,” which involves hiding in specific places that he outlined as safe zones and following the school security plan.

He said often there are times when an individual’s judgment is called for and a plan just doesn’t work.

Sometimes that will involve making a decision to run away from the school, although he stressed the purpose of a lockdown is to remain safe behind locked doors and safe spaces.

He said the students in Parkland were not able to effectively hide due to materials and desks situated in rooms that prevented their hiding from the assailant.

‘Work the plan’

“Hoping this doesn’t happen to you is not a plan. Work the plan that you have. A good decision right now is better than a perfect one five minutes from now,” Delaney said.

He told school officials what killers often look for and pointed out common school vulnerabilities throughout a typical day.

He said a last resort is fighting an intruder—and offered tips in the event that becomes inevitable.

“Don’t be a passive observer to your own murder,” he told teachers. He also offered specifics on hiding, lockdowns, and fighting, and communicating with law enforcement during a lockdown.

To point out some of what went wrong—security-wise—at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., on Feb. 14, 2018, Delaney used a video graphic simulation that highlighted the path and timing of the killer after he breached school security and went throughout three floors of Building #12, killing 17 and wounding 17 others—all students and teachers he could see through classroom door windows or who crossed his path.

Delaney said there were repeated security failures on many levels that led to the carnage, including a failure to stop the killer who approached the building and was clearly identified by security patrols as an “unauthorized” visitor to the campus.

Delaney cited several school personnel who tried to stop the killer during his rampage but were in turn killed by him.

On June 5, one day after Delaney’s talk, former Marjory Stoneman Douglas school resource officer Scot Peterson—who did not go into the school to confront the gunman—was arrested on 11 charges due to his inaction during the massacre.

Former Woodcliff Lake resident Alyssa Alhadaeff, then 14, was killed in the shooting, after having been shot 10 times, according to Lori Alhadeff, her mother.

‘Alyssa’s Law’

Gov. Phil Murphy signed Alyssa’s Law in February requiring panic alarms in elementary and secondary schools.

At another point, Delaney showed a video of a woman—filmed on closed circuit security footage—who appeared to hear a gunshot and walked casually into the next office to look out the window as the gunman soon burst into that office looking for his intended victim.

He said the woman later admitted she knew the sound she heard was a gunshot but did not believe it and therefore took no immediate action.

“Believe it’s happening,” he repeated. He said even if you are familiar with guns and what a gunshot sounds like, because of sound echoing down a hallway it’s difficult to tell where a gunshot is coming from.

Delaney remained after the session to continue discussing security issues with teachers and others.

In March, the Prosecutor’s Office Safe Schools Task Force, composed of five subcommittees, issued a 24-page report providing diverse recommendations on school security aimed at reducing the risk and impacts of a school shooting in a county school.

The report focuses on recommendations and actions to be taken in mental health, private sector, legislation and policy, and an accreditation program for certifying a Safe School.

‘Doubt causes deviation’

“A lack of understanding of what to do in an unanticipated situation inevitably creates doubt in the effectiveness of the recommended action and security plan. In turn, doubt causes deviation from the plan at a time when strict adherence is critical. This leads to poor decision-making and may create a vicious cycle of worsening situations. Ultimately, an individual may find him or herself in a position where deviation from the security plan causes the chances for survival to drop exponentially with each bad decision,” according to the report.

In addition to law enforcement efforts, many county school, mental health, and private sector professionals have been working to address the dangers presented by active shooter situations. The task force said it brings these professionals together to identify and implement best practices.

Delaney previously said the task force considers the school training courses critical for implementing effective school security. The other two courses offered focus on mental health in schools and school risk assessment and building security.

School officials can sign up for the courses at bcpo.net by clicking on “Education Presentations.”

The task force report notes “all recommendations, policy, protocols and trainings should emphasize the critical importance of the ability to quickly and effectively put the school in lockdown and hide out of sight behind locked or barricaded doors in a violent threat situation.”

This month the Prosecutor’s Office plans to pilot a cell phone app called LiveSafe in four towns, including Tenafly, to help improve anonymous reporting of suspicious or threatening behaviors, cyber-bullying and at-risk individuals.