For anyone who watched the PBS period drama “Downton Abbey,” the following century-old scenario might conjure up memories of the tragic love story of Lady Sybil and Crawley family chauffeur Tom Branson.

However, in this cautionary tale, which tells of Tenafly’s own brand of aristocracy, “marrying out of your set” has a much different outcome.

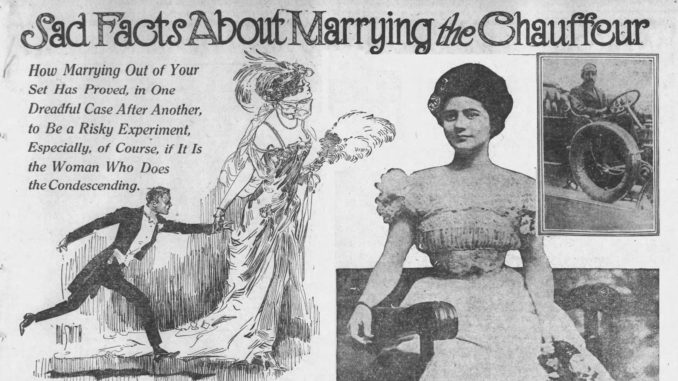

A syndicated article and photo spread—shown above, in part—appeared in newspapers across America in December of 1919, detailing cases in which wealthy young women had married the family chauffeur with disastrous consequences.

“Frequently in the movies and in a certain brand of literature, the heroine is the millionaire’s daughter, who, impelled by what she mistook for the great power of love, steps out of her own fashionable circle to marry her father’s lowly employee,” the article begins. “And always we are likely to be assured by the author of these pleasant romances that they lived happily ever after.”

But, the writer warns, in real life the result of marriage between classes is not always sunshine and roses.

“In fact, several spectacular romances have ended most disastrously of late. Many notable cases where the millionaire’s daughter wearied of her hero after a few years of married life, have come to light to jar the sentiments of the optimist.”

The author cites the case of Elizabeth C. Coppell of Tenafly, who married the family chauffeur, Robert D. Connors, in 1914. She was 50 years old to his 32.

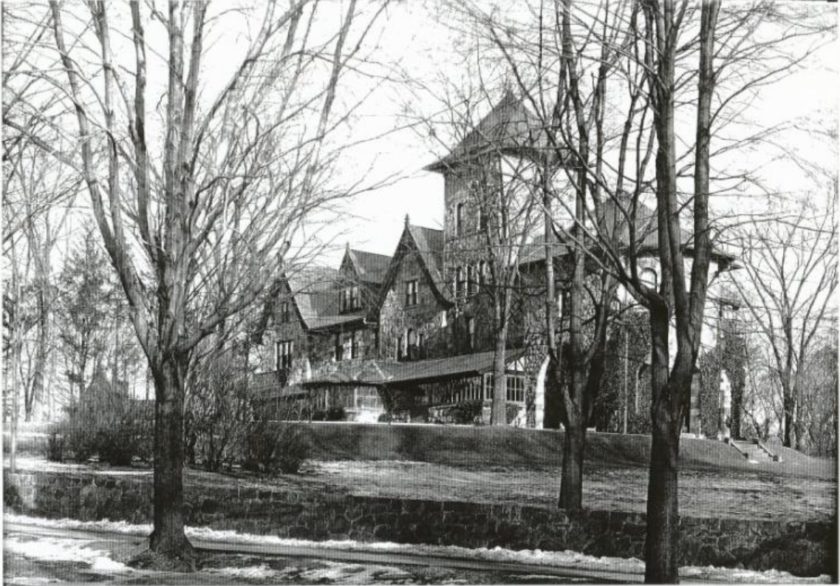

Elizabeth was one of eight children of millionaire banker and railroad builder George Coppell and wife Helen. The Coppells’ country mansion was called The Towers and was on the southeast corner of Engle Street and East Clinton Avenue in Tenafly.

By 1914 Elizabeth’s parents had died, and as the eldest daughter and unmarried, she was entitled to live at the Tenafly estate. Robert Connors had been the estate’s manager and chauffeur for seven years, and he and Elizabeth had gotten to know each other well during that time. They eloped, having told no family members or servants of their plans. Afterwards the newlyweds returned to The Towers. In Tenafly the gossip spread like wildfire. Newspapers from coast to coast picked up the story of the wealthy middle-aged heiress who married a younger working man.

The Coppell family scorned the match and the marriage caused a rift between relatives. Further, the Coppell siblings maintained that as she was now married, Elizabeth had forfeited the right to call The Towers her home. They turned to their lawyers and demanded that Elizabeth either buy out their portions of the estate, or sell back hers.

“The bride at the time defended her chauffeur husband,” the article states, “characterizing him as ‘one possessing unusual intelligence and many gentlemanly qualities.’”

“I love my husband and respect him,” Elizabeth told reporters in 1914. “I wish to say that he is a gentleman, although his station in life was humble. If he had been a rich man no objection would have been made to my marriage. Money covers a multitude of defects.”

Elizabeth sold out her interest in The Towers for a considerable sum and built a new home on Hudson Avenue at Knoll Road in Tenafly. The cost of the new home was reportedly $40,000, equivalent to over $1 million today. She named the estate “Wildwood.”

“Why should we fuss about The Towers? It is big enough for a dozen families and our new house will be far better suited to us. We are now free of the Coppell family and all litigation,” Robert Connors told a New York Tribune reporter in 1915.

The former chauffeur, meanwhile, bought an auto garage in Tenafly and ran it rather successfully, along with a taxi cab business—he did it, he said at the time, to prove to the world that he was not married to Elizabeth for her fortune.

“I want to prove to my wife’s brothers and sisters that I didn’t marry her for her money,” he told the Tribune. “I have always been able to make a living and I can continue to do so. The Coppells tried to drive us out of Tenafly, but they can’t do it. We are here to stay.”

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper raved, “Miss Coppell, daughter of a late millionaire of Tenafly, N.J., seems to have got a man for a husband in Chauffeur Connors. He’s running six taxicabs, taking in $100 a day, and building a house in which there will not be a dollar of the Coppell millions. That is good Americanism.”

The marriage had seemed like a storybook romance, but after a few years things took a downward turn.

At the end of 1919, newspapers reported on the failed relationship. That October, Elizabeth kicked her husband out of the house, involving the Tenafly Police in seeing him ejected. Far from a private matter, the marital spat was aired as front page news throughout the country.

Elizabeth filed for divorce in December, accusing her husband of having an affair with a young woman who was working in a hat shop opposite the Tenafly railroad station. The alleged mistress was just 21 years old. Robert had been the administrator of the woman’s late father’s estate.

At the divorce trial, a neighbor in Tenafly testified that he had seen Robert leaving the young woman’s house at all hours of the day and night, and that they had loud parties that prevented him from sleeping.

As the Connors’ marriage crumbled, Robert slept in a back room at the hat shop—he said he was entitled to, having given the young woman a $1,000 loan to open the place.

Still, while Robert admitted to business dealings and a friendship with the young milliner, he denied any romantic relationship between them. He added, however, that the marriage to Elizabeth was not what he hoped. The elder woman lived a quiet life and spent most of her time knitting, he said, explaining that her idea of fun was having a minister and his wife to dinner. The divorce was final in 1920.

Elizabeth passed away just three years later, in November of 1923.