MONTVALE, N.J.—George Merrill, eighth-grade social studies teacher at Fieldstone Middle School, says his students are famous but don’t know it:

“Well, famous to future historians,” he says.

Those historians will see Merrill’s students through their own “primary sources” around the Covid-19 pandemic.

Merrill says the Smithsonian Institution—the world’s largest museum and research complex, in Washington, D.C.—is taking in some of the projects, and he’s in talks with Rutgers University about that public institution taking other pieces.

The students have been documenting their experiences, which include not only life amid the pandemic but their awareness of the political landscape.

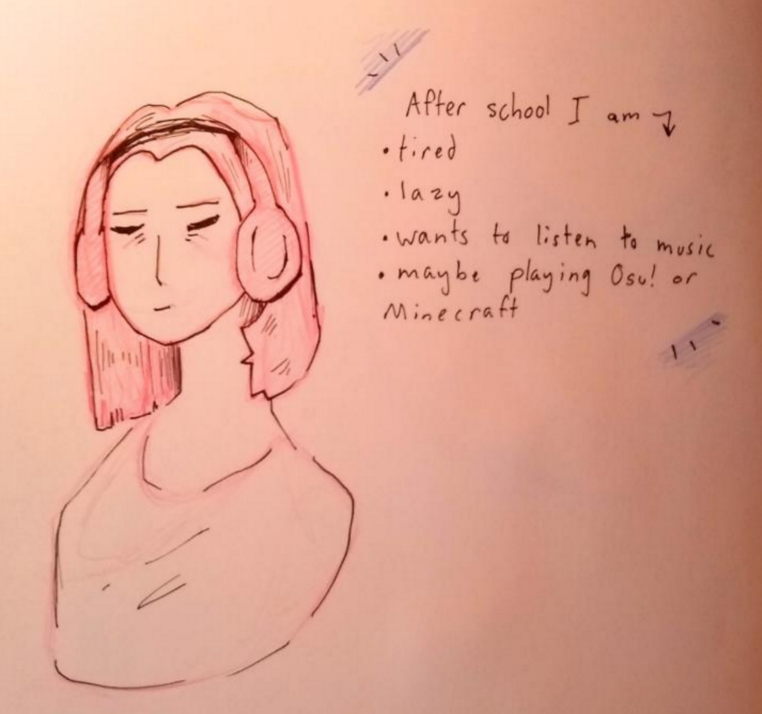

The work consists of video, photo, illustration, and written diaries “that explain how they saw their world change at this unique time.” It’s informed by a study of what teens and others were going through in two previous pandemics going back centuries.

“The goal of the project was for students to understand the importance of bias in their primary sources,” Merrill told Pascack Press on Nov. 25. “In the modern age, there is a lot of information out there so it is important to support students as they look for bias within news stories, events, and other information.”

He had the teens complete a self-reflection about their lives then keep Covid-19 diaries. He said Lauren Lynch and John McGinley on faculty worked with him to develop this assignment.

Merrill said primary sources “have helped students to understand that the past is always someone’s perspective… As they wrote their journals or completed their projects we discussed our own points of view.”

Merrill said his students “really took the task to heart and dived into their experiences. Some spoke of the fear that struck them in the beginning but generally subsided throughout the summer.”

Others, he said, took pictures of covid-related messages around the Pascack Valley—by law, you must wear a face mask for entry; curbside pickup only; stay six feet apart, and so on—and spoke about how these signs might instill a sense of safety or apprehension during visits to local shops.

Yet other students made quarantine survival videos, “showing how they passed the time or engaged with new skills.”

Merrill, who has worked in four school districts and is in his second year at Montvale, says his students have proved “incredibly resilient.” He adds they’re “kind, hard-working, and dedicated to making this atmosphere work. The students have gone above and beyond to make sure they do their best.”

Through the assignment, his students “were really able to understand their own spot in history,” he said.

The desired effect, he said, is “to have students understand they truly are living history and historians will look to their diaries to better understand them.”

In contrast, when you write a research paper, you are creating a secondary source based on your own analysis of primary source material.

Some of the illustrations the kids produced show how face masks and Google Meet affect their lives; how ballots, Black Lives Matter, and the Nov. 3 election registered to them as global concerns; and what they imagine other kids feel. Among them: worry, anger, sadness, ignorance, paranoia, fatigue, knowledge, and calm.

Beating bias

As part of their work on the unit, his students read letters from doctors dealing with the Spanish flu, also known as the 1918 flu pandemic, which infected 500 million people in four successive waves.

They also reviewed records left from the Antonine Plague of 165 to 180 AD, also known as the Plague of Galen. They found a lot to compare and contrast.

“The doctors of 1918 often didn’t use masks when treating patients. The Romans had no idea that masks helped stop diseases from spreading,” Merrill said.

One “teenager” the students heard from wrote about her experience missing school in 1918 and how she missed her teachers and friends. “My students related to that aspect,” Merrill said.

Asked what other contemporary examples of primary sources on the Covid-19 pandemic there might be for our posterity to note, he said social media has been a big asset in looking at the lives of students.

However, he said, “Social media is not an authentic view because of the social constructs around it.” Indeed, there is a growing body of scholarship showing how artificial—how contrived—the social media realm is, with implications for youth mental health.

Another source, he said, is formal writing and documentation from the government. “But rarely do we have access to teenage diaries, thoughts, or experiences during life-altering events.”

In addition, he said, “Polls allow a glimpse into the nation and how [respondents] feel about the virus.”

As The New York Times explained in a piece this June, amid protests there and worldwide, “The scope of what some museums now call ‘rapid response collecting’ has expanded significantly in recent years. Curators often mingle with crowds, scoop up fliers and ask people to part with signs, or perhaps a piece of clothing.”

In the piece, Aaron Bryant, a curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, told the Times, “It is critical that we collect so this moment does not get lost. We talk to people so we don’t forget their stories. History is happening right before us.”

In the same way, there are curated archives and exhibitions of primary sources around the events of Sept. 11, 2001, all reflecting deeply personal points of view.

In students’ own words:

- Zeynep said, “If something is biased you might only be getting one side of the information. Or it might make one side look better than the other. It is not a good idea to use a biased site because it does not give the perspective of both sides. Primary sources help people relate in a personal way to events of the past and promote a deeper understanding of history as a series of human events.”

- Gowri said in part, “It is important to recognize bias because if you’re biased to one thing then you will forget to think about if it was the right choice or not.”

- Noah was succinct: “It is important to recognize bias because if you don’t you could get scammed.”

- H. Foley said the study of bias “makes me do more research and look more deeply into what I look at, especially if I am using it for writing or an essay/project.”

- Keira found that information online and in ads is often misleading. “Learning about bias and claims has helped me find good information. I now can recognize bias and make sure a claim is accurate. I look for signs of extremes such as always, never, and everybody. I can also fact-check the information against other sources.”

- Michael said, “Learning about bias shows how much information can be skewed. Claims online can be biased but not technically incorrect, due to differences in perspectives.”