[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]

BY KRISTIN BEUSCHER

OF NORTHERN VALLEY PRESS

Tenafly, New Jersey — Tenafly multi-millionaire John S. Lyle had been known to make news headlines during his life. One of the richest men in Bergen County in the late 19th century, he was a prominent landowner, merchant and philanthropist of the era. Employed as the vice-president of Lord & Taylor, Lyle owned property from Knickerbocker Road to Jefferson Avenue, bordered by West Clinton Avenue and Riveredge Road. There’s still a Lyle Avenue and Lylewood Drive over there today.

While his first wife Elizabeth was 22 years his junior, she preceded Lyle in death, passing away in 1907. After her death, Lyle hired a nurse, Miss Julia G. Hannon, to work in his household. Three years later, in 1910, the wealthy nonagenarian and his nurse eloped, stealthily boarding a train to New York City. He was 92 and she was 31 years old. At the time, Lyle’s fortune was estimated at about $20 million—or about $500 million in today’s money. The elopement was the juiciest piece of gossip in Tenafly, as neighbors spread the news and speculated on the bride’s motives.

Of course, Lyle was already an old man when he remarried, and Julia ended up a rich widow in 1912 after less than three years of marriage.

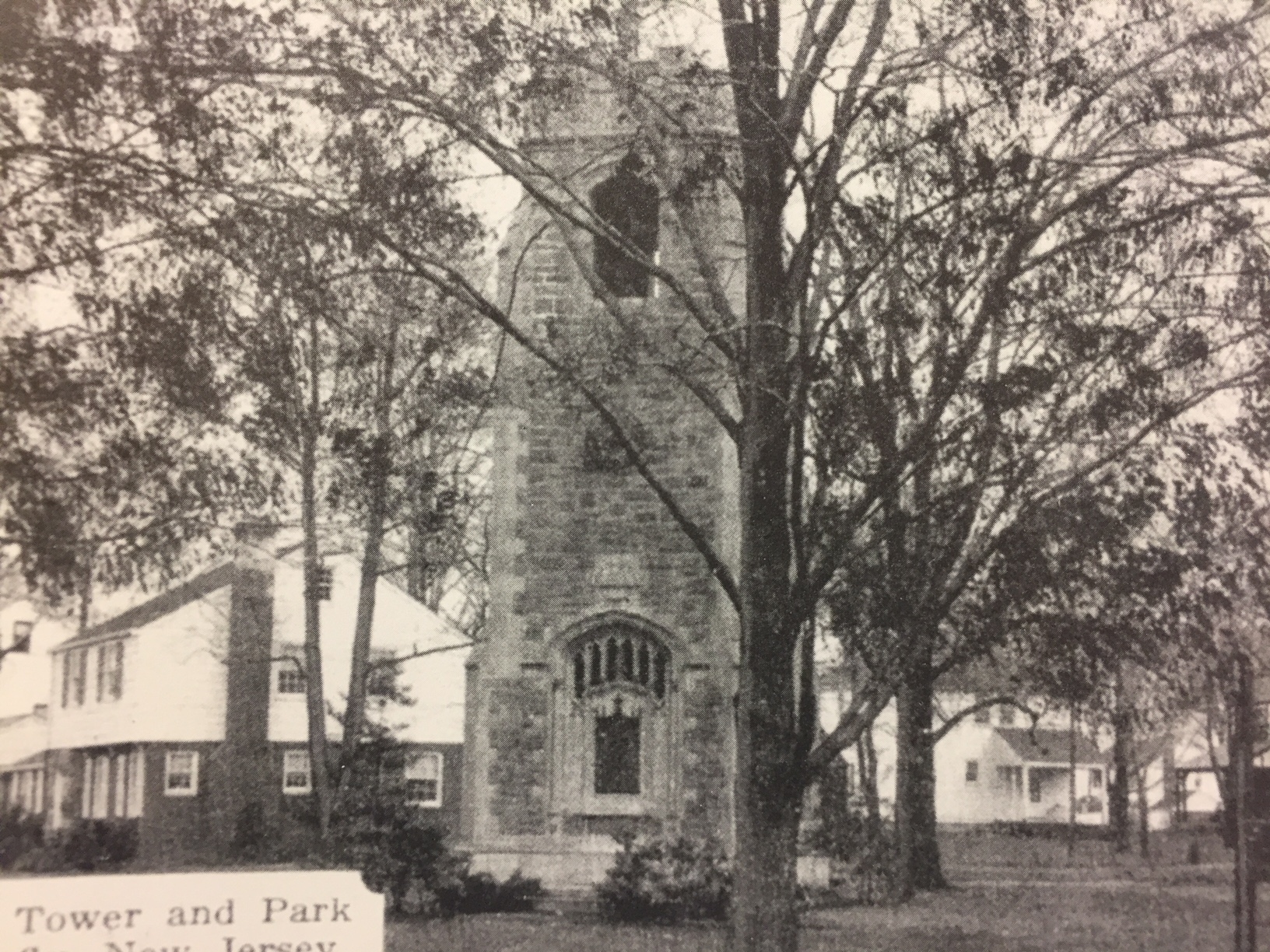

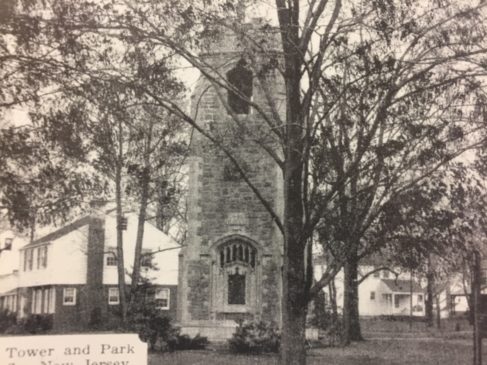

In memory of her husband, she had a 50-foot stone bell tower built on the Lyle estate, near the corner of Knickerbocker Road and West Clinton Avenue. Dedicated Oct. 22, 1913, it contained a big bell weighing 2,000 pounds, plus eight smaller ones. Its chimes sounded every 15 minutes, both day and night, in addition to playing hymns.

While many people in Tenafly enjoyed the chimes, others couldn’t stand them—especially in the middle of the night. In January of 1914, a contingent of angry neighbors filed an injunction in the Jersey City Chancery Court seeking to have the bells silenced during sleeping hours.

“About the chimes there is a vast difference of opinion in Tenafly, several residents certifying that their music was so pleasant as to aid in the enjoyment of comfort, rest and sleep, whereas Mrs. Alice M. Bailey [who lived opposite the tower] swore that the chimes had robbed her of comfort and peace and had impaired her digestion and nerves. She said that she had tried stuffing cotton in her ears, and that she had actually had to go as far as Atlantic City to get some sleep,” The New York Times reported Jan. 20, 1914.

The New York Sun quoted another neighbor as follows: “Those chimes? Don’t ask me about them. I am so thoroughly angry and indignant that I can’t talk. If you lived as near them as I do you wouldn’t have to ask what the trouble is. Yes, they ring every 15 minutes all night long, with ‘Auld Lang Syne’ and everything else mixed in by somebody who doesn’t know one note from another. You ought to hear it; it’s great.”

Edmund Wakelee, counsel for the complaining neighbors, had this to say: “Some of the neighbors are failing in health through lack of sleep. They say it is bad enough to have the chimes boom out the hour at 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning, but to have it accompanied by ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers,’ ‘Adeste Fideles’ or some other hymn is beyond endurance, much as they love those old hymns.”

Said one neighbor, Henry Brenton: “I came to Tenafly to have quietness. I am so nervous that even the rattle of a teaspoon makes me jump.”

On Nov. 17, 1914, Mrs. Lyle herself appeared in the chancery chambers to defend herself. The New York Sun reported that the court room was filled with Tenafly neighbors and curiosity-seekers. The widow, who said she was not yet out of mourning, was dressed in black and purple.

She said her late husband loved chimes, and it seemed as though people enjoyed them.

“On Sunday afternoons when hymns are played at sundown it attracts automobile parties all the way from New York,” she said. “I have seen as many as a dozen near the tower at one time. In fact there are so many that it is often embarrassing.”

Over 20 witnesses testified that they found the bells to be very pleasant.

The end result was a compromise. The judge’s ruling on Jan. 4, 1915 allowed the Lyle memorial chimes to sound at 8 a.m., noon and sunset on weekdays, and at 10 a.m. and sunset on Sundays. The ringing every quarter hour was stopped, and the bells were silenced at night. Tenafly could sleep soundly once again.

In February of 1915 Julia Lyle remarried. She wed a London lawyer, Alexander Wenyon Samuel, in a small New York ceremony. Samuel, a widower, had met Mrs. Lyle only a month earlier. This time the groom was even several years younger than the bride. They spent much of their married life in England.

In 1920, those bells that had so rattled Tenafly were removed from the tower and donated to St. Cecilia’s R.C. Church in Englewood.

The Plainfield Courier-News reported on Oct. 8, 1920 that Mrs. Lyle-Samuel had tried previously to give the bells to Mount Carmel Church in Tenafly, “but they were declined with thanks, the church authorities fearing renewed protests against them.”

[slideshow_deploy id=’899′]